Ten Biggest Latin America Market Entry Blunders

And practical advise on how to avoid them.

BY JOHN PRICE

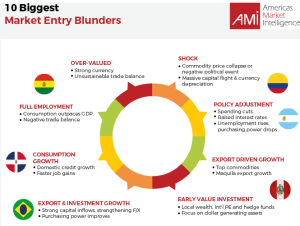

Over the last 30 years, Americas Market Intelligence senior consultants have led more than 4,000 client engagements in Latin America. Along the way, we have witnessed many a blunder when it comes to entering markets in Latin America. To help companies learn from the mistakes we’ve observed while conducting market research, competitive intelligence and analyzing Latin American risk, we created a top 10 list of market entry mistakes.

#1: Entering the Market at the Top of the Cycle

Most companies enter new markets around the world once they show a 3+ year positive track record. Latin America is inherently cyclical because its citizens and companies squirrel away half their savings outside the region, leaving them chronically short of capital and reliant on international loans, repayable in dollars, which they service through the export of volatilely priced commodities. The average boom cycle in Latin America lasts 4-7 years. Waiting halfway through the cycle before investing cuts your returns in half. When a LatAm country enters a down-cycle, voters tend to eschew populism and embrace fiscally prudent policies, signaling to investors to start buying assets.

The degree of cyclicality of an emerging market depends on several factors:

- The greater the diversity of a country’s dollar income, the less cyclical its growth

- The more price elastic a country’s export mix, the more cyclical is its growth

- Well-developed domestic capital markets and pension systems reduce capital flight and volatility

- Healthy volumes of dollar reserves reduce economic volatility

The benefits of early cycle entry are many:

- Assets are cheaper and their owners more malleable to ceding control, financial and managerial – an absolute necessity for any successful acquisition.

- Managerial talent is cheaper and more available. Experienced, multilingual managers and engineers in Latin America are scarce and salaries quickly climb later in the business cycle.

- Clients, partners, and vendors are all more attentive, flexible, and interested when you arrive in a downtime versus a boom period.

- Negotiating optimal investment terms with the host government will prove much easier in an economic tough spot than when you have to queue to meet with mid-tier bureaucrats in a growing economy.

#2: Starting in Brazil or Mexico Because They Are the Biggest

Most companies first enter Latin America through its largest markets, Mexico, or Brazil. That may make sense for some products or services whose demand is only yet developed in Latin America’s largest, most advanced economies. But Latin America’s largest countries are costly and complicated pilot markets for a regional entry strategy.

Brazil is attractive because your competition there may be weak or inefficient, but Brazil is also Latin America’s most complicated, bureaucratic business environment with onerous local regulations, a myriad of taxes to report, costly labor regulations and social taxes, a prohibitive cost of capital, an expensive real-estate environment, poor infrastructure, crippling traffic, and a conflictive legal environment. All together, these impediments are often referred to as the custo brasileiro. Most foreign entries take three times longer to reach positive returns in Brazil versus any other Latin American market.

Mexico is far easier to enter as a market than Brazil, but as a result, the competition is a lot fiercer. Furthermore, local competitors, who after 30 years of NAFTA (USMCA) free trade, are consolidated and lean, too often operate in direct violation of Mexican labor and tax laws, giving them a leg up over multinationals that tend to be held to a higher standard. Despite boasting a modern entrepreneurial class, Mexico’s political class, at its middle ranks, is woefully unprofessional and often corrupt. While most foreign firms refuse to play, Mexican firms may be more comfortable navigating the corrupted contractual arrangements of government procurement and permitting.

The smarter move may to be cut your teeth in a mid-size or even small Latin American market, such as Chile, Peru, the Dominican Republic, or Panama where the learning curve is less costly, competition remains weak but red tape is not too onerous.

#3: Feeling Obliged to Joint-Venture or Buy a Local Company

There are very few places left in Latin America where there is a regulatory obligation to enter the market via a joint venture (J/V). Most governments have given up on protecting strategic industries from foreign investors. So why do companies continue to subject themselves to the pain and hardship of a J/V when entering LatAm markets?

The truth is that some Latin American companies, originally targeted as acquisition targets somehow convince their suitors to structure the deal as a J/V, normally to keep the founding family employed at the new firm—big mistake.

Cross-border joint ventures rarely work anywhere in the world due to the clash of cultures asked to share power and decision making. Acquisitions should be made outright or at least with controlling interest. Furthermore, it is imperative for the majority buyer to exercise his right to hire and fire all levels of personnel. Founding family members, with a few notable exceptions (usually in sales), make poor employees. They are presumptuous, rebellious, usually overpaid and often under-qualified. They should be quickly replaced by locals hired on merit and forced into a non-compete in exchange for the sale of their shares. What sounds like vindictive advice is only prudent. Family-owned companies in Latin America are sold precisely because their reliance on nepotistic hiring practices (hiring those they trust rather than the most qualified) prevents them from growing and evolving. It is important to root out a culture of nepotism and replace it with meritocracy. By doing so, mid-level employees, who worked for years under the yoke of family and friends of the founder, will finally fulfill their potential.

Purchasing a controlling interest in a company provides a jump start on capturing market share, but in Latin America, it comes with huge legal costs and regulatory obligations, particularly those embedded in labor laws. Seniority is protected in most jurisdictions: as such, laying off an employee of 20 years can cost 1-4 years in severance pay. Even after calculating for the hard costs of acquisition, there are the softer costs of restructuring and integration as the buyer tries to impose its own corporate culture over its acquisition.

There are many companies in Latin America worth buying but in a lot of product categories, the multinational brand entering the market already enjoys cache and name recognition. Scaling up operations can be done by outsourcing local manufacturing and relying on 3rd parties to execute sales execution, neither of which requires purchasing a company. Going alone may be the simplest path but does require excellent local support from professional firms as well as layers of support from the head or regional office.

#4: Awarding Market Exclusivity to a Single Distributor or Agent

Most Latin American markets are highly centralized, with anywhere from 60-90% of wholesale activity centered in the capital city. However, three countries are not structured as such: Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia. In those markets, it is almost impossible to find any rep, agent, wholesaler or distributor with true national coverage and reach—though they might insist otherwise when you meet them at a trade show.

Beyond the geographic market diversity of the largest Latin American markets, penetrating these markets requires diverse sales channels, including:

As sales channels have diversified, national distribution has grown more complex, requiring greater skill sets. Few global brands are ever satisfied when dealing with a single national distribution partner. Either that firm lacks true national coverage via traditional channels and/or lacks experience and expertise when it comes to digital marketing methods that support emerging sales channels.

If you are serious about achieving market penetration in these markets, then you will have to invest to some degree your own national marketing function, complete with personnel and expertise on the ground to help shape how your brand is promoted, margins are managed, and regulations are complied with. You will need multiple partnerships, ranging from regional wholesalers to big box key accounts, to e-commerce fulfillment specialists, to digital marketing agencies and Value-Added Resellers (VARs).

#5 Neglecting to Visit the Market on a Regular Basis

Many global consumer brands in niche products neglect Latin America because they lack the international management bandwidth to properly oversee their sales efforts in the region. International sales managers who are focused on North America, Europe, China and elsewhere are almost relieved when a Brazilian or Mexican distributor shows up offering to rep their product. After a flurry of visits to the market during the due diligence and start-up phases, Latin American markets are often ignored, particularly when left in the hands of sophisticated local distributors.

National distributors—particularly in Brazil and Argentina—are adept at defending their autonomy and at discouraging visits from headquarters. Ignore their charms and visit the market regularly. Local stocking distributors are known to switch branding labels to their own, sell outside their boundaries, price the product in violation of global guidelines, bribe customs officials to import shipments—all manner of activities that jeopardize the integrity of your brand. Perform regular market audits, including mystery shopping of your product or service in each major Latin American market. Be sure to build penalties into your distribution agreements against those actions that threaten your brand.

#6 Sending One of Your Own to be Country Manager

Exercising control over your subsidiary or sales office in an emerging market is a sensible instinct to employ, but the country manager is the wrong instrument of that control. In Latin America, like most emerging markets, the country manager is the tip of your marketing, PR, and government relations spear. He or she should be local or someone who has lived in the local market for years, speaks not only the local language but is sensitive to local customs and enjoys personal relationships with powerful local players in business and government.

The country manager is your top salesperson, your brand spokesperson, your government relations manager, an inspiration to employees and your number-one problem solver. All those roles rely more on local knowledge than on corporate legacy. It takes far less time to indoctrinate a local hire as to your corporate culture than it takes for one of your own company veterans to learn the customs and develop contacts in a local market.

The ideal vessel of corporate control in your Latin American subsidiary is the CFO, traditionally the second strongest C-suite position in Latin corporate culture. Not only does the CFO oversee budgets but he or she also leads strategic planning, and often compliance issues as well. The CFO is the most logical interlocutor with headquarters on the most sensitive issues that can undermine your overseas operations.

#7 Refusing to Extend Credit to LAC Importers, Customers and Suppliers

American and Canadian firms are notoriously conservative when it comes to issuing credit to customers overseas, particularly in emerging markets like Latin America where the costs and bother of collecting debt are onerous. European firms are somehow less encumbered by the practice. Even when sourcing from emerging markets, multinationals make the mistake of setting painful payment terms of 60-90 days to their underfinanced vendors.

Credit is costly and scarce in Latin America, in spite of all the recent strides made in the region’s banking systems. Local brands and European suppliers understand that Latin American distributors and importers simply cannot finance enough inventory to serve their potential demand. Holding back credit limits the ability of your product to penetrate the market. Failing to extend credit for the sale of your service may effectively price you out of the market in a region where consumers and businesses live pay period to pay period.

Multi-latinas, the term used to describe large Latin American multi-nationals, know how to bank their own vendors. Their default payment terms are often 90 days, but they will pay vendors within 72 hours in return for hefty discounts of anywhere from 1-5% per month, i.e., 3-15% discount versus normal 90-day payment terms. Similarly, they extend credit to their customers, be they intermediaries or B2B, extracting onerous interest income from downstream clients. If done right, they earn more money with their finances than they do with their core operations. Foreign companies can learn from such savvy.

#8 Avoid E-Commerce Channels at Your Peril

E-commerce is a well-oiled machine in the American market. The same cannot be said in Latin America’s smaller markets, where fulfillment is often cross-border. Merchants in the US, Europe and Asia frequently receive requests, if not orders from Latin American customers. Many dread such enquiries because the fulfillment of a single purchase export to Latin America can be a logistical nightmare. In one mystery shopping exercise AMI carried out, single-product shipments to some two dozen markets around the world—including emerging markets in EMEA and APAC—revealed that logistics hurdles were greatest when trying to penetrate Latin American markets, including delivery delays, lost product, and bribery demands from customs officials.

E-commerce is not easy for vendors but is already an important channel in spite of its challenges because of the user friendliness from a consumer’s point of view. There are 1/8 the number of brick-and-mortar retail square meters per capita in Latin America compared to the US. For people living outside the largest 1-2 cities in a Latin American country, product choice is limited, and niche products are simply unavailable. E-commerce is the channel that serves those people as well as the growing middle class which lacks the time to battle epic traffic levels to buy what they seek in a physical store. E-commerce fulfillment is growing more sophisticated, reliable, and cheaper in Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. Other domestic markets will soon follow. Cross-border ecommerce will take longer to improve but the prize is big enough that solutions will be found.

#9 Choosing to Ignore Latin America’s Massive Grey Markets

The 800-pound gorilla in the room for product managers trying to build a marketing strategy in Latin America is the influence of the grey market, defined as a channel through which legitimately manufactured products are illegally imported (evading tariffs) and illegally sold to customers (evading VATs). In every major Latin American city, there are multiple grey markets. Some look like large street fairs, others are housed in physical stores. In some product categories, the grey market might represent 60+ % of national sales—the Peruvian athletic shoe market, for instance.

Often dismissed by multinationals, grey markets can be surprisingly sophisticated, providing money back guarantees for a limited warranty period, even extending credit to well-known customers.

Another form of grey market sells pirated products like brand rip-offs – clothing, luxury accessories, pharmaceuticals, spirits, personal care products, auto parts, consumer electronics, and jewelry. As a former LAC General Manager for Levis Straus once quipped at a regional conference, “Latin America may not yet be a world-class market, but one can certainly realize world-class losses there.”

Expect little or no enforcement support from host governments. Grey marketers have cleverly woven themselves into the institutionalized corruption of customs and immigration, always one of the least transparent areas of government. Their political might give grey markets a degree of legitimacy and formal players must take heed. Pricing policies for product distribution need to recognize the competitive pressures of the grey market. Latin Americans prefer to buy from formal channels but will only pay so much of a premium over the grey market alternative.

Some products have enjoyed unexpected success by openly embracing grey market channels. Clorets, one of the top selling chewing gum brands in Mexico, is almost universally sold via grey markets, using hundreds of thousands of street peddlers to sell the gum.

Any serious analysis of a market’s potential—along with competitive threats—must include the relevant gray markets.

#10 Exiting Markets in Tough Times

Latin American importers, reps and distributors frequently complain that when the going gets tough, the Americans pack up shop and abandon the market. Leaving a market sends a traumatic signal to customers and suppliers. Unless you are certain of leaving a market for good, it is far wiser to trim down to a minimum, maintain some brand presence and continue to service existing customers as cost effectively as possible.

Abandoned customers do not forget and may not come back when you decide you want to reopen a market. Additionally, the cost of market entry and exit is such that once in, it is cheaper to maintain a holding pattern than pull up stakes. Last but not least, keeping a skeleton staff employed will provide the necessary platform upon which to grow quickly when viable conditions return.

John Price is the Managing Director of Americas Market Intelligence. With 20 years of experience in Latin American market intelligence consulting, Price has supervised nearly 1,200 client engagements and advises clients in more than 20 countries across Latin America. He can be reached at jprice@americasmi.com

This article was first published by AMI. Republished with permission.