Sinaloa Cartel War Hits Culiacán Economy

As Sinaloa Cartel war rages on, an economy bleeds dry in Culiacán, Mexico.

BY VICTORIA DITTMAR

AND PARKER ASMANN

InSight Crime

One morning in September 2024, Ana Rosa Sánchez* arrived early to begin her morning routine at a seafood restaurant in Altata, a small fishing village in the Pacific coast state of Sinaloa. But as she awaited her first clients, her phone started buzzing. Culiacán had erupted into chaos with reports of gunfights, killings, and arson attacks.

Without thinking twice, Sánchez closed the metal doors to the restaurant and locked them shut. She wouldn’t open them again for four months.

Altata is located just about 40 minutes west of Culiacán, the capital city of Sinaloa. For years it has been a favorite destination for locals to spend a weekend enjoying the beach, eating fresh seafood, and listening to the state’s famous banda style of music.

But that sense of calm vanished starting on September 9, 2024, the date that many in Sinaloa have marked as the unofficial beginning of the internal war between the Chapitos and Mayiza, the two most powerful factions of the Sinaloa Cartel.

The fighting began after the controversial arrest of the famed capo Ismael Zambada García, alias “El Mayo,” and has centered mostly around Culiacán, the Sinaloa Cartel’s historic operational base. But it was only a matter of days before the intensity of the clashes cleared out nearby towns like Altata and paralyzed a large part of the economic activity in the area.

“I’m very adventurous, and I’m not afraid of anything. But this, this scared me,” Sánchez told InSight Crime one April 2025 morning at her restaurant, which did not have any other customers inside.

An April 2025 morning on the boardwalk in the fishing village of Altata, located in the municipality of Navolato, Sinaloa. Credit: Victoria Dittmar

After eight months of relentless fighting, the situation has shown no signs of improving. With almost daily displays of extreme violence, Culiacán and surrounding villages like Altata are confronting historic economic losses. This massive financial gap is due in no small part to the loss of illicit drug trafficking money, which for many years helped sustain a significant part of the local economy.

For many experts consulted by InSight Crime, this may signal a breaking point.

Closed Doors and Vacant Streets

Despite the absence of official data to measure the scale of the economic impact of the Sinaloa Cartel’s internal war, the financial losses could be as much as 2% or 3% of the state’s gross domestic product, according to estimates from Cristina Ibarra, a local economist and president of the Federation of Economics Colleges in Mexico.

“We are absolutely living through an economic depression,” she told InSight Crime.

The restaurant and hotel sectors were the first to be hit hard by the loss of clients, largely due to the self-imposed curfew that many adhered to in the face of the daily violence breaking out across Culiacán. During the first week of the conflict alone, when the economy practically ground to a halt, Ibarra estimated the losses totaled nearly 3.5 billion pesos (more than $175 million).

They haven’t stopped since.

“Since September there hasn’t been a single day where we’ve had more than 10% occupancy,” said the receptionist of a 3-star hotel attached to a popular shopping center in the center of Culiacán. “People don’t come here anymore, not for tourism or business.”

At least 350 restaurants have been forced to close, according to Miguel Taniyama, a local restaurant owner and member of the National Restaurant Industry Chamber (Cámara Nacional de la Industria Restaurantera – CANIRAC). An untold number of other informal businesses like street food stalls have also closed down.

The restaurants that have managed to stay open have been forced to close early, let go staff, and look for new ways to keep themselves afloat, such as offering breakfast. Staff members have also seen their tips fall dramatically.

“This ‘narco-pandemic’ is the most brutal thing we have lived through,” Taniyama added. “It’s worse than the COVID-19 pandemic.”

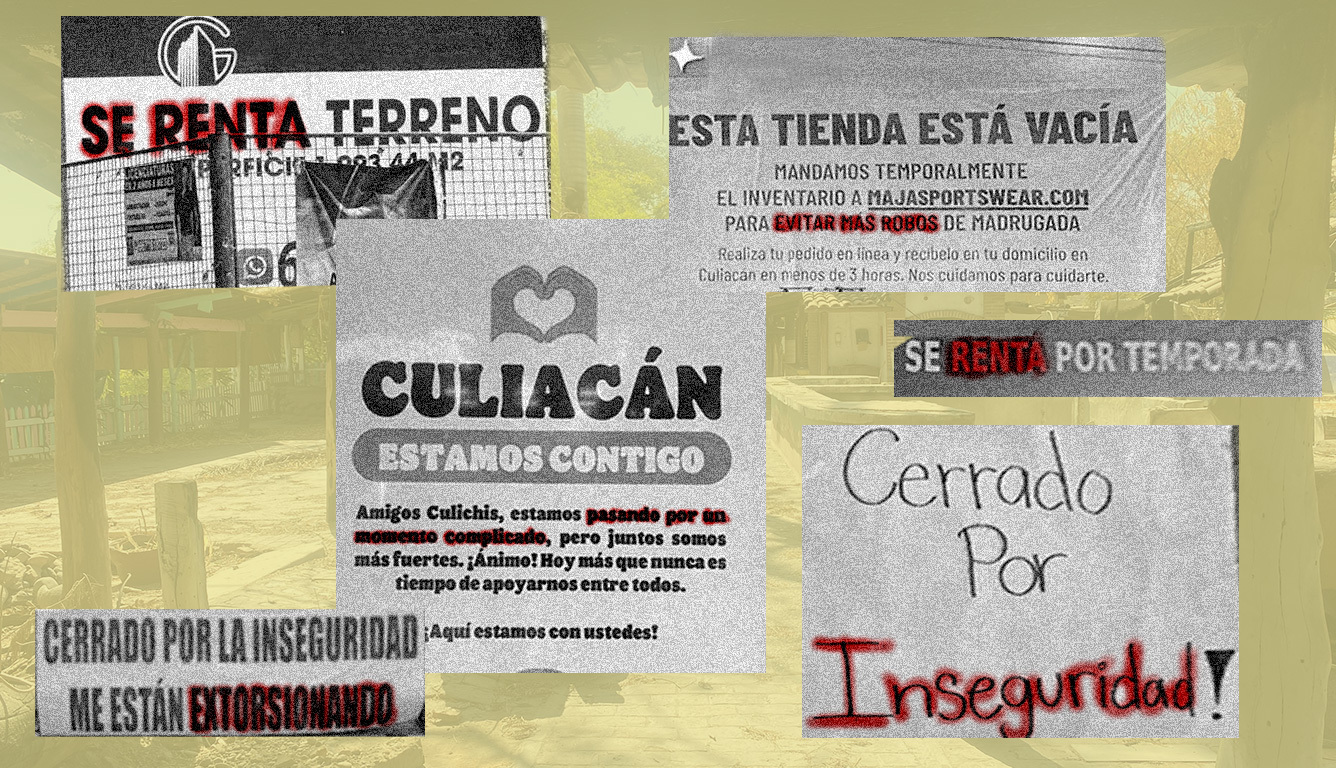

Small- and medium-sized businesses were the next to collapse. The city is filled with shuttered and vacant buildings that once housed convenient, clothing, tech, and stationery stores. Recently, one pharmacy chain announced it was closing 40 locations just in Culiacán.

There is still no official data on the number of jobs lost due to the Sinaloa Cartel conflict. However, experts like Ibarra and Martha Reyes, the president of the Mexican Employers Confederation (Confederación Patronal de la República Mexicana – Coparmex) in Sinaloa, estimate that between 12,000 and 14,000 jobs were lost between September 2024 and April 2025 alone just in Culiacán.

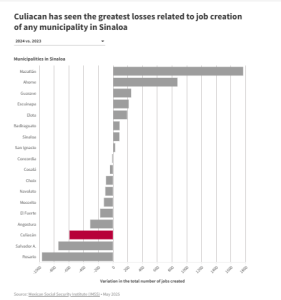

What’s more, the conflict has halted any possibility of generating new economic opportunities. Culiacán created 591 less formal jobs in 2024 compared to 2023, according to data from the Mexican Social Security Institute (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social – IMSS). And in just the first three months of 2025, there were 6,643 fewer job opportunities than there were during the same time period the year before.

Ibarra added that today she estimates there are around 4,700 fewer entrepreneurs than before the conflict started and almost 41,000 new people now earning only the minimum wage.

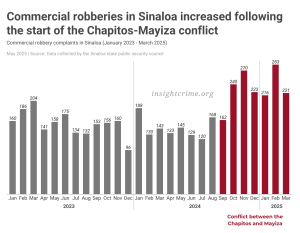

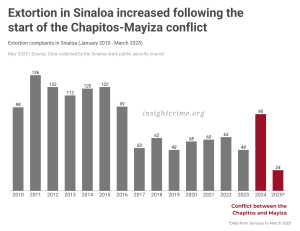

However, local businesses are not just impacted by the loss of clientele, but also targeted violence. Since September 2024, complaints for extortion and robberies have increased across Sinaloa, reaching levels not seen in the past eight years.

The consequences have been devastating. Taniyama, the local restaurant owner, estimated that between 20% and 30% of restaurants closed as a form of self-protection because they could not afford to pay extortion or because of direct threats they received.

At the end of October 2024, for example, a popular restaurant called Chuparrosa Enamorada that served regional food was burned down. The owner was murdered days later. That same month, two other sushi restaurants were set on fire and several other businesses were shot at.

What remains of the Chuparrosa Enamorada restaurant in Culiacán after being set ablaze. Credit: Victoria Dittmar

The ‘Narco-Economy’ Vanishes

In Culiacán, there is another sector of the local economy that has been severely diminished due to the violence: luxury goods and services.

For many experts and locals consulted by InSight Crime, there is one clear explanation. The internal Sinaloa Cartel war has forced many traffickers and their associates from the city. But with them disappeared an economic bubble fed by illicit financial flows.

From high-end restaurants to narco-influenced fashion boutiques, the city’s most costly and exclusive neighborhoods are now filled with closed stores and “for rent” and “for sale” signs. The doors of many businesses frequently associated with money laundering activities have also closed down, such as money exchanges, used car dealerships, and barbershops.

It is not hard to see the influence of this “black economy.” Since 2016, Sinaloa has consistently ranked among the Mexican state’s with the lowest salaries, according to IMSS data. However, the state has the sixth-highest purchasing power in the country, and in 2024 it was among the top three states with the largest growth in this area, according to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social – CONEVAL).

“This discrepancy can only be explained by a significant influx of resources that come from outside the formal economy,” said Ibarra, the economist.

The businesses were almost too perfect: they facilitated money laundering while at the same time satisfying consumer demand with unreasonably high earnings. It is easy to identify these operations, according to local business leaders consulted by InSight Crime. The businesses are usually built in a matter of months with multimillion-dollar investments that would take any regular business years to secure.

“Prices in Culiacán are inflated and way higher than what the average person can pay,” said one member of a local business group. “We live with this ‘narco-inflation’ without even realizing it.”

For now, the rupture of this bubble has disrupted supply chains, eliminated employment opportunities, and halted financial flows — including for businesses that have no ties to these illicit operations.

Even Sánchez, the restaurant worker in Altata, has felt the impact. She said it was clear when members of criminal groups stopped spending their money in town.

“Whether you like it or not, they bring a lot of money and that allows us to create jobs,” she told InSight Crime.

A Golden Opportunity

Even with the current economic collapse and future uncertainty, several business people interviewed by InSight Crime said the current crisis represents a golden opportunity to look beyond drug trafficking and rebuild Sinaloa’s economy.

The present conditions are ripe for change.

In certain rural communities, the fall of marijuana and poppy cultivation forever ruptured the dependency farming families once had on the economic opportunities provided by crime groups. And in urban centers like Culiacán, the explosion of violence and innocent victims provoked a broader rejection of drug traffickers, even in certain social circles where they were previously tolerated and at times admired.

“This should be the breaking point,” said Taniyama.

But it won’t be easy. For decades, Sinaloa’s economy has depended almost exclusively on agriculture and cattle ranching with very little diversification outside those industries, according to Reyes, the Coparmex president in Sinaloa.

In addition, the US government’s recent designation of several organized crime groups in Mexico — including the Sinaloa Cartel — as foreign terrorist organizations created greater barriers for attracting foreign investment. It’s unlikely companies would be willing to take the risk, both reputational and legal, of operating in a region associated with these groups.

Still, Reyes told InSight Crime that the present moment offers “a unique opportunity to reinvent ourselves.”

“But it is going to take some work,” she added. “We need to find what added value Sinaloa’s economy can provide.”

Marcos Vizcarra contributed reporting for this article.

This article was originally published by InSight Crime. Republished with permission.

*The name of this source has been modified for security purposes.