Sheinbaum: The Energy Risks

The five main energy risks of a Claudia Sheinbaum Administration.

BY ARTHUR DEAKIN

Claudia Sheinbaum’s 20%-plus polling advantage materialized into a landslide presidential victory, putting an end to AMLO’s six-year administration that all but froze private investment in both renewable energy generation and transmission infrastructure. Many energy investors and operators are optimistic about a new administration, but Morena’s excessive power could make it harder than expected for foreigners to do business in the country. In preparation for our webinar on the topic, AMI’s energy practice outlines the five major risks to the energy sector during the next six years:

1.

A potential constitutional reform of the energy sector. With Morena (and its coalition partners) securing a supermajority in both chambers of Congress, and their control of 75% of the nation’s governorships, AMLO’s initial attempts to overhaul the 2013 energy reform are more likely to succeed. For the month of September, he will have new congressional and elected officials and governors in office while he remains President (until October 1st), giving him a narrow window to pass controversial reforms (he has proposed 20 constitutional reforms). If AMLO somehow fails to reverse or overhaul the 2013 energy reform in September, President Sheinbaum will have at least three years (till midterms) to make changes. That will sow doubt among some investors.

2.

A doubling down on Pemex. Sheinbaum has vowed to refinance the state oil company’s U$100+ billion in debt and venture Pemex into new sources of revenue (e.g., lithium, geothermal), while simultaneously continuing AMLO’s legacy of propping up state companies. Mexico subsidized about 35% of gasoline’s retail price in 2022, using funds from its oil revenues. If Sheinbaum keeps subsidies in place to prevent the rise of gasoline prices, as well as continue to finance Pemex losses and mounting interest costs – Mexico’s coffers and Pemex bondholders are likely to suffer.

3.

Increased dependency on foreign fossil fuels. With a large percentage of natural gas and refined oil already coming from the U.S., any serious disputes between the two countries could force Mexico into uncomfortable concessions in exchange for continued US supply. As noted above, it is unlikely Mexico will be able to reverse its oil production decline as Pemex continues to struggle financially and technically.

4.

Billions of dollars in lawsuits from international energy companies could hinder private investment and nearshoring. In February, the government announced the expropriation of a hydrogen processing plant in Hidalgo state, bought by French company Air Liquide for roughly 50 million euros. These disputes are likely to enter into the “panel stage” under the USMCA treaty, leading to multi-million-dollar settlements and continued tensions between the US and Mexico. This lack of contractual and legal clarity, coupled with grid reliability challenges (i.e., blackouts, and congested transmission lines), could diminish Mexico’s nearshoring opportunity.

5.

Criminal extortion delaying projects and hindering profitability. Since the electoral process began in September 2023, more than 200 public officials, politicians, and candidates were killed, several of which came at the hands of cartels. Although criminal extortion is even more common in the mining industry, the building of large energy projects such as LNG terminals and gas pipelines, will overlap with drug routes within Mexico. Pinpointing where those routes are, and how to avoid them, are essential in reducing violence and extortion.

Despite these risks, Sheinbaum could also introduce specific policy changes that could help grow the production of renewable fuels, distributed generation, and renewable electricity supply in the country. The potentially optimistic outcomes of this new administration include:

- Growth in renewable energy development. Energy investors, developers, and manufacturers will reignite their Mexico operations as Sheinbaum seeks a 50% renewable target by the end of her term in 2030, up from the current 15% penetration. Although Sheinbaum has called for $13.6 billion in new electricity infrastructure investment and 80 GW of solar and wind power, the extent of her divergence from AMLO’s nationalist policies is still unclear. To have a chance at achieving this target, the new president will need to reform Mexico’s permitting process, which can take 5-7 years for a solar and wind project, twice as long as some Latin American jurisdictions.

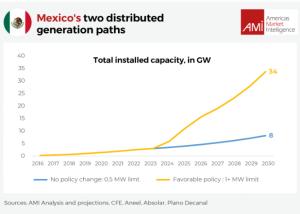

- Increased distributed generation limit to 1 MW. To achieve the above objective of 50% renewables, we believe Sheinbaum could increase the maximum threshold for distributed generation projects from .5MW to 1MW. This would allow for an easier grid connection for larger on-site projects that supply power to industrial facilities. Mexico’s 3 GW of installed distributed generation capacity is a far cry from Brazil’s 26 GW, where the maximum threshold is 5 MW. As seen in the chart below, AMI projects that a favorable policy shift could increase Mexico’s installed distributed generation capacity to 34 MW by 2030, a fourfold increase when compared to a scenario in which policies remain the same.

- Approval of a biofuel law. Sheinbaum is more likely than any of her political predecessors to approve a biofuel law or mandate, as clean fuels are a personal interest of hers (she spearheaded a biodiesel plant in Mexico when she was mayor and wrote a paper entitled: “Potential of biodiesel from waste cooking oil in Mexico.”)

- Contractual clarity for renewable energy developers. Despite the supermajority shaping up in Congress, Mexico’s Supreme Court struck down AMLO’s electricity reform in January 2024, which prioritized energy dispatched by state-owned CFE at the expense of independent power producers (IPPs). This could hinder any major energy reform laws and pave the way for IPPs and developers to restart looking at solar and wind opportunities in the country.

- Accelerated LNG development. Since proposed Mexican LNG terminals use U.S. natural gas as feedstock, they require U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) approval for exports to nations that lack free-trade agreements (FTA) with the United States. Recently, the US DOE announced a moratorium on those export permits. Planned LNG export terminals in Mexico that already have DOE approval (e.g., Mexico Pacific and Sempra’s Visto Pacífico) will likely see accelerated development as they can “replace” the supply deficit created in the U.S. market.

As Sheinbaum prepares for her inauguration on October 1st, many things are still likely to change. Yet, there are clear steps that investors and operators can start to take to shield their assets and position themselves to maximize profitability in the country. Local intelligence, gathered by on-the-ground experts, will help companies do so.

Arthur Deakin is Director of the Energy Practice at Americas Market Intelligence.

This article was first published by AMI. Republished with permission.