Mexico FDI: The Election Impact

Impending return to single-party governance hurts FDI attraction.

BY DAVID A GANTZ

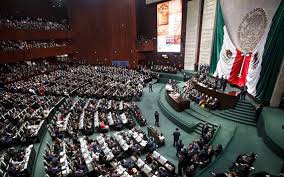

While the election of President Andrés Manuel López-Obrador’s endorsed candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, on June 2 was anticipated, her victory margin of over 30 points against the main opposition candidate, Xóchitl Gálvez, and securing more than 58% of the total vote, was a surprise to many observers. Similarly, although it was not overly surprising that the president’s party, Morena, achieved a supermajority in the Chamber of Deputies with 372 out of 500 seats, most pollsters and observers did not foresee Morena coming within a few votes of achieving a supermajority in the Mexican Senate, with 83 out of 128 seats. This means López Obrador only needs to persuade two or three opposition deputies in order to obtain the necessary 86 votes for a supermajority in the Senate, thereby securing Morena’s control of Mexico’s entire federal government.

While Mexico faces a potential return to single-party governance, its ability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) in the coming years is diminishing. This issue brief examines how potential legislative and constitutional changes implemented by López Obrador before the end of his term could impact Mexico’s investment climate. Additionally, López Obrador’s ongoing aversion to foreign investment in the energy sector and Mexico’s continued dependence on U.S. natural gas could contribute to an unfavorable investment climate in the near future, particularly if Mexico reverts to single-party control. As one observer recently suggested, López Obrador’s “lame-duck reforms will hurt Mexicans, drive investment away and wreck relations with the U.S.” They would also conflict with multiple provisions of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), in which the parties, among other things, resolve “to establish a clear, transparent, and predictable legal and commercial framework for business planning that supports further expansion of trade and investment.”

Proposed Legislative and Constitutional Changes

López Obrador and his supporters have promised that — as soon as the new Congress is installed in early September and before Sheinbaum takes office on Oct. 1 — they will seek to take full advantage of Morena’s congressional supermajorities. In mid-June, López Obrador reiterated his intent to enact legislation that would allow for the dismissal of the current (largely independent) Supreme Court and other federal courts with elected judges — approximately 1,600 judges in total — to be replaced by judges of his and Morena’s choosing. Additionally, López Obrador and his party officials plan to enact other major changes that could threaten the rule of law and further weaken Mexico’s already turbulent investment climate.

This scenario assumes that the loose Morena coalition will hold together after Oct. 1, when López Obrador is no longer president. If even a few of the legislators who are currently part of the Morena coalition — perhaps those who oppose a return to a pre-2000 single-party governance reminiscent of Hungary, India, or Iran — do not support these changes, any major legislative initiatives not enacted prior to Oct. 1 could be deferred or abandoned. Whether this possibility is realistic or overly optimistic remains to be seen.

In February 2024, López Obrador submitted to the Chamber of Deputies a package of 18 constitutional amendments and two legal reform initiatives aimed at modifying the functioning of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, as well as the electoral system, among other objectives. If all the legal and constitutional reforms are enacted, they would eliminate various autonomous constitutional bodies and regulatory agencies and streamline the structure of the federal public administration sector. Significantly, the changes would further entrench the near-monopoly of the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) and modify the power sector by establishing constitutional prohibitions on activities such as fracking and open-pit mining. Many of these proposals were previously introduced earlier in López Obrador’s term but failed due to adverse court decisions or Morena’s lack of a supermajority in the upper house. At that time, the opposition parties united to defeat these measures.

Declining Foreign Direct Investment

In a country where foreign direct investment has been discouraged by nearly six years of López Obrador’s efforts to roll back the 2013 energy sector reforms and reestablish virtually complete state monopolies for Pemex and the CFE, the result has been increasing investor uncertainty and looming electric power shortages. This uncertainty would be further exacerbated — and the rule of law further eroded — if the proposed judicial reforms noted above are implemented.

Additionally, serious water shortages in some parts of the country, uncertain access to natural gas, pervasive corruption, strengthened drug cartels, reduced personal security, generally low productivity, and expanded government military control in customs, transportation, and other sectors are contributing to an unfavorable investment climate. Consequently, FDI is likely to remain stagnant or decline from its current levels.

Since 2019, FDI has remained essentially unchanged at around $33 billion annually, despite significant nearshoring investment opportunities resulting from U.S. efforts to diversify production and supply chains away from China. For the first half of 2023, one bank estimates that of the $29 billion in direct investment, 78% corresponded to the reinvestment of profits, 15% to transactions between companies, and only 7% to new “greenfield” investments.

Ongoing Electric Power Challenges

Although it is reasonable to hope that Sheinbaum will assert her independence once she becomes president on Oct. 1, achieving such independence is likely to be very difficult, particularly in the short to medium term. Sheinbaum, who holds a Ph.D. in environmental science, is reputed to have a stronger interest in green energy compared to López Obrador and most Morena members of Congress, who are deeply committed to Pemex and oil. However, she lacks López Obrador’s charisma and his overwhelming influence over Morena party officials, both in Congress and in state and local offices. For example, Morena now controls 23 of 32 governorships, and those governors effectively owe their positions to López Obrador.

Mexico’s energy industry is facing severe short- and long-term challenges in large part because of López Obrador’s aversion to FDI in the green power sector. This has resulted in the effective expropriation of a series of wind and solar projects owned by American, Spanish, and Italian companies, designed to strengthen the CFE’s near-monopoly. Additionally, López Obrador’s government pressured one of Mexico’s largest foreign investors in clean energy, Iberdola, to effectively withdraw from the Mexican market and sell its assets to the CFE.

The CFE’s lack of funds and technology to expand Mexico’s electricity production or power transmission capabilities has resulted in a series of short-term brownouts in some parts of the country and continued dependence on fossil fuels including natural gas (around 55%), coal (about 6%), and dirty Pemex fuel oil (about 14%). Less than 10% of the country’s energy is generated from solar and wind. Mexican authorities, such as the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), have also largely ceased authorizing independent power projects, which would allow large factories to secure their own energy supplies independent of the CFE. While “distributed generation” projects are allowed without CRE authorization, the paltry 0.5 megawatt limit (compared to the U.S. cap of 5.1 MW) significantly restricts their use, “presenting a significant hurdle for companies whose energy consumption often exceeds this limit.” Because of this, some experts are calling for an increase in the 0.5 MW cap.

In January 2024, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that an electricity law favoring state-owned utilities over private firms violates constitutional guarantees of free competition in the power sector. However, given Morena’s effective soon-to-be supermajorities in Congress and its impending control over the Supreme Court, whether this decision will hold remains uncertain.

In my view, any new investor in Mexico expecting a dependable, reasonably priced supply of even partially clean electric power for the medium or long term, or access to a functioning judiciary, is being overly optimistic. Any multinational enterprises committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2040 or 2050 should understand that establishing facilities in Mexico may significantly challenge their global commitments for several decades.

Dependance on US Natural Gas

To some extent it has been feasible for manufacturing enterprises in the Mexican border states to purchase electricity in small quantities from the United States, principally from Texas and Sonora. These enterprises, along with the CFE, are heavily dependent on natural gas imported from the U.S. This dependency has increased in part due to a 30% decline in Pemex’s natural gas production between 2009 and 2023. In 2022, Mexico imported about 5.7 billion cubic feet of U.S. natural gas per day, accounting for about 69% of Mexico’s natural gas consumption, according to some estimates. Fortunately, the U.S. is likely to have an excess supply of natural gas to sell to buyers in Mexico for the foreseeable future. However, much of Mexico beyond the northern border states lacks the necessary pipeline infrastructure to transport imported gas. The reluctance of foreign investors to finance new pipelines in Mexico due to the risks associated with Mexico’s petroleum sector suggests that reliance on imports of natural gas will not change anytime soon. Ironically, despite a decline in petroleum production, Mexico flared nearly 10 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually as of 2022. This is largely due to insufficient pipeline infrastructure to transport the gas from the southeast to the major consumption areas near the northern border, a situation exacerbated by Pemex’s lack of financial resources.

Other Disincentives for FDI

In addition to energy sector reforms, other initiatives proposed by López Obrador are expected to further increase the arbitrariness and unpredictability of investing in Mexico. If approved, López Obrador’s administrative initiative would grant the executive branch the power to revoke or modify administrative licenses or certifications at any time, including after issuance. These actions would be based on the government’s interpretation of vague concepts such as “public interest,” “national security,” or “protect(ion) of individuals’ fundamental rights.” Such vagueness could foster increased corruption. Moreover, under the new system of elected judges, court review is likely to become largely ineffective.

At a time when the likelihood of arbitrary government action is increasing, foreign investors also have less comprehensive protection under the USMCA compared to its predecessor, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In many cases, U.S. or Canadian investors’ only recourse is the Mexican courts or administrative tribunals, which may lack independence from the government due to the planned reforms that would replace many of the judges with candidates chosen by López Obrador, Sheinbaum, or other Morena politicians.

Canadian investors also no longer have access to independent third-party investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). While U.S. investors in government contracts related to petroleum, electric power, transportation, telecommunications, and certain infrastructure projects retain NAFTA-like protections, all other investors must exhaust local court or administrative remedies before becoming eligible for ISDS. Furthermore, the scope for challenging regulatory actions is significantly decreased, as many international arbitral tribunals appointed under USMCA authority lack jurisdiction to review arbitrary actions (under the “fair and equitable treatment” provision) or indirect or creeping expropriation.

Probable Return to Single-Party Government

As of mid-2024, it is uncertain whether López Obrador and Morena, with at least tacit support from Sheinbaum, will succeed in enacting their proposed changes to Mexico’s laws and constitution, thereby further weakening the investment climate. However, there is a strong possibility that whatever is not accomplished in September will take place under Sheinbaum soon thereafter, provided she feels obligated to do so and the Morena coalition remains intact. López Obrador, Sheinbaum, and Morena appear to have sufficient power to return Mexico to a single-party government, reminiscent of the nearly 70-year period prior to 2000 when the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) exercised near-complete control over the presidency, Congress, judiciary, and administrative agencies, sometimes referred to as the “perfect dictatorship.” Despite hopes that fewer Mexican voters would favor a return to autocratic governance, the election results on June 2 indicated otherwise.

A key post-election question is whether Sheinbaum will be able to act independently of López Obrador on critical issues such as increasing Mexico’s supply of electric power, clean or otherwise. Many potential investors may adopt a wait-and-see approach, at least until the end of 2024, to judge whether Sheinbaum’s presidency will improve, harm, or maintain the current investment climate, especially considering López Obrador’s attempted reforms in September. While Sheinbaum’s background as a climate scientist may give hope to some, others may be concerned that López Obrador will continue to exert significant influence over Congress and public opinion well into her term, potentially leading to skepticism and reduced new investment in 2024 and beyond.

Mexico’s Bleak Foreign Investment Horizon

As noted above, it will not be clear until after Oct. 1 whether the legal and constitutional changes backed by López Obrador will successfully overturn many elements of Mexico’s current democratic system. However, it is clear that these changes will exacerbate rather than repair Mexico’s poor investment climate and give the government and Morena greater control of all aspects of Mexican life. Even initial actions on energy, such as increasing the current limit on distributed generation projects from 0.5 megawatts to 5, 10, or even 25 megawatts, would be beneficial. Yet, such improvements alone are unlikely to convince potential investors to make long-term commitments given the high risk of arbitrary government interference. Without improvement in Mexico’s energy availability, which López Obrador has generally opposed for nearly six years, any other steps that Sheinbaum takes to reassure potential foreign investors will likely be unpersuasive unless she demonstrates her independence from her predecessor when the good of the country demands it.

President Sheinbaum’s ability to address the nation’s energy issues would be significantly enhanced if even a few members of the Morena coalition, such as members of the misleadingly named “Green” Party, were to challenge López Obrador and recognize that Morena’s opposition to private investment in clean energy is inconsistent with both green principles and Mexico’s obligations under the Paris Agreement. For example, if the so-called judicial “reforms” could be delayed until after Oct. 1, there is a possibility they could be deferred indefinitely.

Mexico’s allies, both domestically and internationally, can only hope that effective energy reform will progress and that both the judicial dismissals and continued administrative arbitrariness will be thwarted. If so, Mexico’s foreign investment prospects may yet stand a chance, but if not, its investment climate is sure to suffer.

David A. Gantz, J.D., is the Will Clayton Fellow in Trade and International Economics at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. He is also the Samuel M. Fegtly Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Arizona’s James E. Rogers College of Law.

This article was originally published by the Center for the U.S. and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute.