Latin America: China’s Trade Strategy

Strategy behind China’s commercial engagement with Latin America.

BY JOHN PRICE

Few issues in Latin America are more polemic than speculating on the true intentions behind Chinese investments in Latin America. There is no refuting the economic benefits wrought by the arrival of over $200 billion of foreign direct investment, a similar level of bi-lateral lending and over $4 trillion in trade over the last two decades. Latin America’s longest-lasting boom period in a half century, from 2003-2013, was almost entirely generated by China’s lust for Latin American natural resources. And yet the reclusive nature of many Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) operating in Latin America combined with a growing distrust of Chinese global aims has people wondering, what is the strategy behind China’s growing engagement with Latin America?

Forcing the hermit nation out of its shell

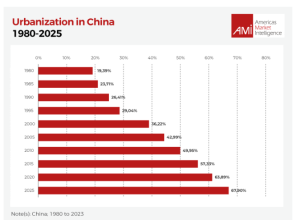

China does not come by international engagement naturally. The hermit nation has a history of recoiling from international engagement, its governments consumed by domestic concerns and uninspired by global exploration. China’s engagement with Latin America began reluctantly but became imperative at the start of the millennium. In 2000, the world’s greatest migration of people in history was under way, the movement of hundreds of millions from rural to urban China. Driven out of their farms by cheap agricultural imports and aggressive land developers, rural Chinese sought work in the city.

As urban numbers swelled, so did unemployment and unrest, with over 1,000 social protests per year in China at the turn of the century. Chinese leadership has always been spooked by social unrest. Their monopolistic political rule is tolerated by the Chinese citizenry if economic growth and full employment is sustained. Blessed with Most Favored Nation trade status and thus low tariff access to the world’s richest markets, the Chinese government subsidized the expansion of large-scale manufacturing, adding to the sizable investments of privately funded domestic and internationally owned manufacturing interests. Quickly, China exhausted its own supply of commodity inputs for its factories — things like energy, minerals, steel, chemical inputs, agriculture — and turned to international suppliers.

Relieving financial & political pressure

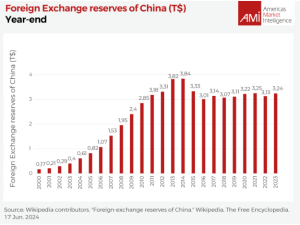

A key part of China’s full employment policy requires that their exporters remain globally competitive, despite rising input costs, now sourced increasingly from abroad. The Chinese central bank has to regularly intervene and buy US dollars to keep the Chinese currency from rising in value, which hurts the competitiveness of Chinese manufacturing. By 2006, China had accumulated over US$1 trillion in reserves, sparking cries of currency manipulation from politicians in Washington and Brussels.

The Chinese needed to secure long-term supplies of raw materials but in 2003, commodity prices began to soar, as Chinese demand outstripped global supply. In the 1970s and 1980s, Japan and South Korea respectively had endured the same supply dilemma. In those decades, commodity prices were lower (in real terms) so those countries locked in suppliers to 20+ year contracts. The Chinese knew they were buying at the top of the business cycle so longer-term fixed price contracts made no sense. Instead, Chinese SOEs used the nation’s abundant supply of dollars to purchase mining companies, energy companies, agricultural assets and other raw material producers around the world. Thus began the Chinese shopping spree in Latin America. It had little to do with Latin America and everything to do with maintaining economic and political stability in China.

Sustaining China’s construction sector

Fast forward to 2008 when the global financial crisis, started in the US, befell the global economy. For close to 18 months, the world’s supply of trade finance dried up. Chinese manufacturers, operating on razor-thin margins, lacked the working capital to fulfill orders for customers in Europe and North America. Millions of Chinese factory workers were laid off, and social protests ramped back up in mainland China. The Chinese Keynesian response was the largest public works project that the world had ever seen. In a span of five years, over 40 subway systems were built, six billion square meters of residential housing was constructed, 50,000 km of highways were built. But the spending spree in China had to end because municipal debt had ballooned, and assets were overbuilt. In the process, China had created the world’s largest construction industry, capable of complex and vast engineering projects, but had nowhere to grow in China. Thus, the belt and road project was designed — not as a master plan to take over the world but to keep millions of Chinese construction workers, engineers and managers employed.

In regions like Africa and Latin America, most belt and road inspired infrastructure projects are designed to help extractive resources get out of the country and onto a shipping vessel efficiently. This fulfills several aims. It helps lower the input costs of said commodities by lowering transportation costs from Latin American mine/farm/oil patch to Chinese ports. The profitability of these logistics assets (ports, roads, rail lines, storage facilities) is stable thanks to the dollar or Yuan revenue that they directly or indirectly generate. By mitigating currency risk on these projects, Chinese banks can offer very low rates, giving Chinese project bidders a leg up on their competitors. Lastly, these projects help lift the export competitiveness of Latin American economies, which underpins the long-term stability of markets where China has growing investment exposure.

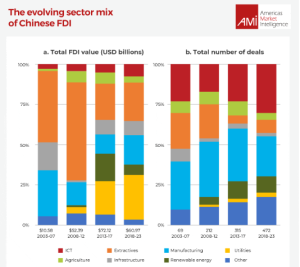

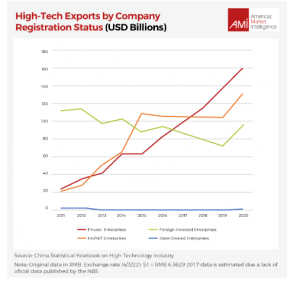

Selling Chinese products & services to middle income markets

The most recent wave of Chinese investment in Latin America (and other middle-income markets) is driven not by state-owner enterprises (SOEs) but by China’s burgeoning private sector, made up of increasingly competitive multinational companies. Since 2020, there are more Chinese companies in Fortune’s global 500 list than there are American firms. Furthermore, the pure private sector share of China’s 100 largest firms climbed to 54% in 2022 before being punctured by government intervention and shrunk down to about 40% where it stands today. But when it comes to China’s exports, private companies dominate. This is especially true with high tech exports (roughly 30% of all Chinese exports) where private capital is responsible for almost 99% of exports.

China is no longer the maquiladora manufacturer that it once was. Foreign-owned companies are responsible for less than 20% of China’s manufacturing exports (versus over 70% in Mexico). Today, there are 52 car companies in China versus 53 in the USA and 13 in Latin America. Chinese brands struggle to penetrate mature, wealthy markets like Western Europe, US, Canada, Australia and Japan, shunned by an increasingly outdated reputation for poor quality and lack of after-sales service. So Chinese exporters have focused on middle-income markets like Latin America, North Africa, the Middle East, southeast Asia and, more recently, Russia. Today, Chinese car brands outsell those from all other countries in Chile and Peru. And when it comes to electric bus and vehicle sales in Latin America (and most emerging markets), Chinese brands are winning.

Like Japan before it, Chinese brands face a dual threat that obliges them to invest in production facilities outside of China. Firstly, many emerging markets (including Mercosur) actively encourage foreign investment in manufacturing by erecting tariff walls. Back in China, the population under 50 years of age peaked in 2008 and has declined since, making manufacturing increasingly expensive at home. For logistically costly (heavy) goods like automobiles, building in China and shipping abroad kills profit margins. Hence BYD, the world’s largest electric car company, has built a factory in Brazil and will soon start assembling in Mexico.

Chinese digital sector leaders

Where Chinese private companies have really penetrated Latin American markets is in the digital services economy. E-commerce, logistics, ride-share, gaming, cloud storage, social media and telecoms are all sectors where Chinese multinationals have sought expansion in Latin America.

AliExpress: The international arm of Alibaba group. Aliexpress anchors its LatAm strategy in Brazil where it has invested billions, though it operates across the region.

Shein: The world’s leading online clothing merchant bet big on Brazil, pledging $150M in FDI. By serving as online store and logistics to textile makers, they enhance and protect the domestic industry.

Cainiao: Cainiao is the international express delivery service under Alibaba. Like its parent company, Cainiao has invested heavily in Brazil, building an impressive domestic and cross-border logistics network. They plan to replicate the ‘Brazil model’ elsewhere in LatAm.

J&T Express: J&T entered Mexico and Brazil in 2022 and hopes to compete in both cross-border and domestics logistics, focused initially on e-commerce.

Yunquna: Yunquna is a high growth unicorn 4PL logistics player that focuses on first and last mile sea and air cross-border logistics, including warehousing.

Huawei: Huawei entered Brazil in 1998 and dominates that market today. Their cloud business has more nodes than any competitor in LatAm. They are constructing data centers in 8 LatAm markets.

Xiaomi: Xiaomi controls 12% of Latin America’s smart phone market and has built a network of online and off-line retail stores to market its products.

Oppo: Focused on Mexico since 2020, Oppo now holds 12% of Mexico’s handset market and will next enter the premium segment.

TikTok: TikTok has over 65 million users in Mexico and close to 200 million in Latin America, one of its leading markets worldwide.

Kwai: Kwai, the international version of Shutterstock, has an average of 45.4 million monthly active users in Brazil. It plans to expand in LatAm.

Tencent Games: Tencent today has tens of millions of gamer clients in Latin America, led by Brazil where they first entered the region.

Didi: Didi is the largest ride-hailing app in Latin America, slightly ahead of Uber in a consolidating market, one of the largest in the world.

The next wave – energy transition

China wants to dominate the clean energy sector and thus far is on track to fulfill that ambition. China is the largest manufacturer of solar energy technology, including solar cells, panels, racks, cabling, and battery storage. At the other end of the supply chain, China dominates as well, since it is the largest miner and processor of critical minerals. Latin America is an important partner in China’s energy transition strategy. The region is home to the world’s largest known reserves of lithium and copper. Latin America’s climate lends itself to highly efficient solar energy generation. Brazil and Chile have developed a regulatory climate to support a viable solar industry. Hopefully soon, other jurisdictions will streamline their permitting and liberate their concession frameworks to also attract investment. Chinese companies will grab the lion’s share of equipment sales for the sector.

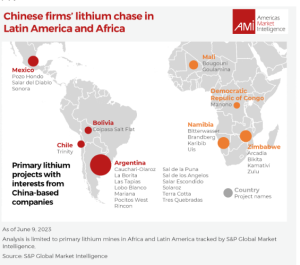

Chinese mining investors continue to gobble up lithium and copper assets where they can. After some conflictive investments that went poorly in Peru, Chinese miners are gradually improving their public image and continue to outbid other miners on these strategic assets. In lithium, Argentina is likely to attract the most lithium investment from China, and elsewhere thanks to its decentralized (provincial level) regulatory framework and the pro-investment policies of the Milei administration which will soon float the Peso.

So what is the threat?

In this article, we have dealt the commercial logic behind China’s investments in Latin America. What began as investment flows dominated by very large Chinese SOEs in search of resources and Chinese employing infrastructure projects has developed into a diversified intersection of two very symbiotic economies. Latin America has natural resources and human capital. China has financial capital, technology and a large consumer base.

Today, Chinese, and HK-domiciled companies often dominate strategic industries inside Latin America, including critical mineral mining, port operations, digital services, logistics and renewable energy. These companies have the ability to collect vast amounts of data related to trade, people movement and money movement. How that data is collected, where it is stored, and who can access it are all points of concern to citizens, governments and private sector competitors. The military and intelligence arms of the US government look on with increasing concern as to the growing presence of Chinese state-owner enterprises (SOE) and private sector companies, making little distinction between them when it comes to their political loyalties and commitment to preserving data privacy.

All of these concerns are valid and will be explored in future analysis. For now, the glass remains half full (as opposed to half empty) for most Latin American business interests and Latin consumers when it comes to the growing presence of China in the region.

John Price is the Managing Director of Americas Market Intelligence. With 20 years of experience in Latin American market intelligence consulting, Price has supervised nearly 1,200 client engagements and advises clients in more than 20 countries across Latin America. He can be reached at jprice@americasmi.com

This article was first published by AMI. Republished with permission.