How DiDi Adapts to Latin America’s Era of Digital Platforms

The Chinese ride-hailing app has acclimated remarkably well to local conditions, challenging simplistic narratives about the entry of Chinese companies into the region.

BY OMAR MANKY AND

NATALIA MOGOLLON

Information and communication technologies have radically transformed the organization of the world of work, to the point where people speak of an “uberization” of the economy. However, it is not Uber but DiDi that is the leading company in personal mobility globally: in 2021, DiDi recorded more trips in China than Uber worldwide. But DiDi’s ambition extends beyond China. For the past five years, the company has begun investing in other markets in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This expansion presents crucial challenges in terms of adapting to environments very different from China’s—such as that in Latin America, which is characterized by high levels of informality in the labor market and problems of citizen insecurity.

This paper explores and analyzes the strategies that DiDi used to establish itself in Latin American countries, including Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Peru. The context in which DiDi arrived in the region differs significantly from the Chinese context. Before DiDi’s entry in late 2019, the Latin American market was dominated by global giants such as Uber and Cabify. That timing also meant that DiDi’s entry was affected by the coronavirus pandemic and restrictions on people’s mobility, as well as the economic crisis faced by the region. Moreover, although the extent varied between cities, the company faced a challenging environment due to protests by taxi driver associations and unions against ride-hailing platforms.

In this context, DiDi implemented adaptation strategies based on three pillars. First, it established strategic alliances with local governments, private companies, and civil society actors to address security issues and promote social initiatives. Second, it adapted to local needs by offering innovative services (such as DiDi Food for food delivery and the DiDi Flex fare negotiation option) and expanding its services to the financial sector through loans and credit cards in countries like Mexico and Brazil. Finally, the company emphasized passenger safety, with rigorous driver verification processes and options for drivers to avoid dangerous areas, while also offering low commissions to drivers and food delivery workers (that is, claiming only a small portion of fares) to gain a significant market share.

This trajectory demonstrates a remarkable ability to adapt, challenging simplistic narratives about the entry of Chinese companies into the region. It also raises key academic questions about the mechanisms of this adaptation and how much it is linked to the specific characteristics of the transportation industry and the unique trajectory of this private company. The case discussed in this paper also raises questions for public policymakers and for other companies in the sector. These questions relate to improving the working conditions for those contracted by the company, formalizing employment, and protecting user data privacy.

Introduction

Information and communication technologies have radically transformed the way that humans work. Artificial intelligence (AI), like tools that facilitated communication channels decades earlier, has redefined workspaces, legal restrictions, and social perspectives on employment. Today’s era is characterized by the ease with which digital platforms connect clients and service providers, often circumventing traditional labor structures that previously defined the relationship between employees and employers, as well as their respective rights. This shift toward more flexible work arrangements has also led to less stable and less secure employment in many areas.

In this context, digital platforms have emerged as crucial actors over the last decade, impacting the lives of millions of workers globally. By affecting a diverse range of workers, including food delivery drivers in South Korea and graphic design professionals in India, these companies have redefined urban work dynamics. Latin America is no stranger to this transformation, having witnessed the emergence and expansion of local companies such as the e-commerce app Rappi (Colombia) and the food delivery app PedidosYa (Uruguay), which compete with global giants like Uber and Grubhub. Cities like Lima, Bogotá, and Buenos Aires have experienced aggressive market entry dynamics combined with global mergers, acquisitions in distant markets by parent companies, and the bankruptcy of new platforms each year. These developments raise important political and academic questions about the impact of technology on labor control, the use of private information, and urban economies.

Against this backdrop, the entry of DiDi Chuxing Technology Company (hereafter, DiDi) into Latin America stands out. As the world’s largest ride-hailing company—with 15 million drivers in 2021 compared to Uber’s 5 million in 2020—DiDi not only represents the expansion of a global corporation in a novel industry but also symbolizes China’s growing technological influence worldwide. DiDi’s entry into Latin America and its subsequent success in the region has significant implications, signaling a departure from the region’s traditional emphasis on mineral resource extraction and large-scale infrastructure projects. Additionally, DiDi’s status as a private company distinguishes it from the more common Chinese state-owned enterprises’ investments in the region, potentially marking a new phase in the evolution of Chinese investments.

This paper explores how DiDi operates in Latin America, examining some of its central characteristics and highlighting its ability to adapt to the region’s features and actors. This analysis presents preliminary findings based on research conducted on drivers and delivery workers in Peru. It also offers a comprehensive overview of how the platform has adapted to various contexts across Latin America. The document is divided into three sections. The first section provides a systematic overview of DiDi’s background in China and the state of digital platforms in Latin America before DiDi’s entry into the market. The second section offers an analysis of DiDi’s entry and adaptation in the region, based on an examination of secondary sources in several Latin American countries and interviews with experts, drivers, and delivery workers using the app in Lima. Finally, the third section discusses the implications of these findings for the development of public policies and academic understanding of the impact of Chinese investments in Latin America.

DiDi’s Origins the Latin American Market Landscape

Latin American countries grapple with common challenges such as inequality, informal labor markets, and stunted economic growth in the post-pandemic era. Despite variations among countries, these shared issues create a complex landscape for the development of the digital economy. Recent data indicates that, in 2023, job creation slowed across the region, and the labor participation rate has not yet rebounded to pre-pandemic levels in several countries. Moreover, it is crucial to consider the region’s historical dynamics, including high levels of income inequality, substantial gender gaps, and rampant urban violence. In this highly precarious environment, platforms must adapt and seize opportunities presented by digitalization while also addressing the need for regulation and social protections.

Platforms do not operate in a social or material vacuum. While Latin America has made significant strides in establishing the physical infrastructure necessary for digital connectivity, it still faces critical challenges in harnessing the potential of new technologies. According to a 2023 World Bank report, although some countries like Brazil and Chile boast broadband coverage rates exceeding 75 percent, others, particularly in Central America, fall below 50 percent. Furthermore, the report highlights persistent gaps in service quality, especially in rural areas and lower-income segments of the population. The cost of accessing digital infrastructure also poses a significant barrier, consuming up to 25 percent of monthly income for the poorest quintile in countries like El Salvador and Ecuador. Against this backdrop, international companies need to adjust their approach, considering that income levels, technological skills, and salary expectations in Latin America differ markedly from those in the Global North.

Another critical feature of the region is the high prevalence of informal labor in the transportation sector and its impact on working conditions. While the Global North has recently seen a rise in discussions about the precarious nature of work on digital platforms, the context in the Global South presents a different scenario. This is not because the working conditions offered by most of these companies are superior, but rather because these platforms emerge in contexts already marked by a large proportion of informal work, limited regulation, and greater workforce precarity. In this landscape, characterized by what Francisco Durand termed a “fractured society” where the boundaries between formality, informality, and illegality are porous, platforms like DiDi find fertile ground for expansion. In areas where state oversight is limited, these companies leverage digital infrastructure to employ a large number of drivers and delivery personnel who are already in a state of informal, precarious work. This raises important questions about the impact of platforms on the quality of employment and the potential for greater employment formalization in a sector historically defined by informal work.

In the context of businesses’ changing organizational logic, Latin American scholars have observed that the platform economy tends to standardize the management and exploitation of labor by circumventing employment contracts and basic labor rights. Companies strive to minimize costs by shifting all service expenses onto workers. Uber, Rappi, and DiDi position themselves as intermediaries with local “partners” rather than as service providers with employees, enabling them to obscure employment relationships. Despite some debates, there have been no significant advancements in labor legislation, with discussions typically focusing more on tax regulation than on labor issues.

This paper aims to provide a more nuanced analysis of platform companies, highlighting the particularities of DiDi and its operations in the region. While the platform economy is often discussed as a monolithic entity, it is essential to recognize that not all companies in this sector operate in the same manner. The business strategies and labor processes of these platforms can vary significantly, even when the core activity is the same, and this diversity greatly influences workers’ experiences and demands. By adopting a comparative approach, this paper raises the questions of how companies like DiDi adapt to different contexts and how their practices may differ from those of other platform companies operating within the same space.

This is crucial because the quality of work generated by platforms and their potential for expansion depend not only on each state’s capacity to regulate them but also on the strategies developed by individual companies. In terms of individual state capacity, it is important to note that the perception and regulation of digital platforms vary significantly across Latin America. In cities like Buenos Aires or Mexico City, with regulated transportation markets and strong taxi unions, the arrival of these platforms generated tensions and confrontation. However, in unregulated markets, such as Lima, it was seen as an opportunity to organize such services privately. This diversity of experiences presented a unique opportunity for platforms, and DiDi, arriving years later, seems to have learned from these varied contexts to adapt its strategies accordingly.

As for individual corporate approaches, before DiDi’s arrival, Latin America had already become fertile ground for ride-hailing platforms, given the region’s rapid urbanization processes, deficiencies in public transport, and the high availability of private vehicles. Companies like Uber, which entered the region in 2013, had already established a presence, with Uber quickly becoming the market leader at 70 percent of market share in over 500 Latin American cities by 2018. In fact, the region became Uber’s second-most important source of revenue, although competition intensified starting in 2017 with the entry of new players like DiDi, Beat, and InDrive. Uber’s market share, indicated by the total number of transport app downloads, had decreased from 74 percent in the third quarter of 2017 to 44 percent by the second quarter of 2019. This significant drop was mainly due to DiDi’s successful entry into the Mexican and Brazilian markets. In the former country, DiDi held 56 percent of market share as of early 2022. Before the coronavirus pandemic, the company was capturing a significant share of the ride-sharing market in the region, with over 1 billion rides completed. In Brazil alone, DiDi is estimated to have around 750,000 active drivers—150,000 more than Uber has in the country. In the food delivery sector, platforms like PedidosYa and Rappi have gained significant popularity. These companies, rooted in Uruguay and Colombia respectively, have expanded their presence far beyond their points of origin. This is a crucial detail of the backdrop against which DiDi began to build its relationships with different social actors.

Two key factors that shed light on how DiDi has adapted to the Latin American market include the impact of the pandemic and the various forms of resistance related to working on these platforms. It is worth noting that the coronavirus pandemic and mass migration—especially from Venezuela to countries like Colombia, Chile, and Peru—created a new group of potential workers. Many of them saw platforms as an opportunity to generate income in a market affected by the public health crisis. In the context of the pandemic, the demand for food delivery and private transportation services increased as thousands of people sought to avoid public transport or going to restaurants. DiDi took advantage of this moment to enter countries like Peru. Furthermore, economic stagnation in the region caused high unemployment. This factor, coupled with the lack of a basic social safety net provided by regional governments, forced many to seek new ways to generate income through platforms.

As for worker resistance, the pandemic provided the impetus for thousands of workers to raise their voices against underlying structural injustices. The landscape is heterogeneous. In countries like Argentina, Chile, and Brazil, platform workers have made relatively successful efforts to organize themselves. These workers’ main demands are associated with low wages and the recognition of labor rights. In other cases, like Peru or Ecuador, the capacity for union organization is very limited, and no strong representative organizations have emerged.62 These varied contexts, marked by differing levels of resistance from traditional taxi unions and the ability of drivers to use multiple apps simultaneously to maximize earnings, present unique challenges for DiDi compared to its dominant position in China.

In summary, in Latin America, DiDi has not only had to face well-established competitors but also adapt to markets with high levels of informal labor, different perceptions of transportation safety, and a constantly changing regulatory framework. In this context, the company’s trajectory represents an interesting case for analyzing how a global platform, with significant experience in the Chinese market, adapts and responds to the particularities of a diverse and dynamic region.

DiDi in Latin America

Since 2015, DiDi has invested in companies around the world, such as Grab (Singapore), Lyft (United States), Ola (India), 99 (Brazil), and Bolt (Estonia) to establish itself internationally.63 In 2018, the company initiated its expansion plan in the Latin American market by acquiring 99, the leading ride-sharing company in Brazil, and launching operations in Mexico, both strategic markets because of their size. From there, DiDi extended its operations to Chile (2019), Colombia (2019), Panama (2020), Argentina (2020), the Dominican Republic (2020), Peru (2020), and Ecuador (2021).

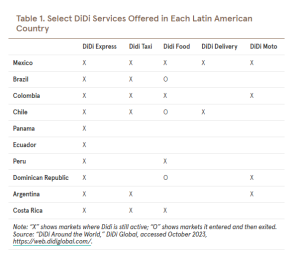

As in China, DiDi has developed various transportation and mobility services in Latin America, tailoring them to the needs and preferences of users in each location. These services include DiDi Express, DiDi Taxi, DiDi Moto, DiDi Delivery (Didi Entrega), and DiDi Food.

In 2018, DiDi ventured into the food delivery market with DiDi Food, aiming to compete with platforms like Uber Eats, Rappi, and PedidosYa, among others. Interestingly, while DiDi Food has gained significant traction in several Latin American countries, the company’s food delivery service has a smaller presence in its home market of China, where other players dominate the sector. The company’s expansion of this service exemplifies its ability to adapt to diverse market conditions. Moreover, unlike its competitors, DiDi publicly emphasized that its vision extended beyond being an intermediary between restaurants, users, and delivery workers. The company stated that its goal was to become a driver of new economic opportunities for the gastronomic industry. According to América Economía, DiDi Food is the only app with a continuous investment program designed to assist local businesses, allowing them to enhance their presence in the app and, consequently, increase their sales. The platform initially launched operations in Mexico and Brazil, marking its presence with a competitive offering that included a wide range of associated restaurants and food options for users. Subsequently, from 2019 onward, it expanded its operations to Chile, Colombia, Peru, and the Dominican Republic, establishing a significant presence in the region.

Despite its initial success, between 2022 and 2023, DiDi surprised the market by announcing the withdrawal of its DiDi Food service from Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and, most recently, Chile. These moves reflect the company’s ability to swiftly adapt to changing market conditions and strategically prioritize its resources. In Chile, the company issued a statement indicating that it had decided to focus resources on strengthening its mobility business, while its other services would continue to operate in the country. Experts consulted by América Economía attributed DiDi Food’s exit from Chile to multiple factors, including the economic impact of the pandemic and the company’s need to concentrate its efforts on markets with higher profitability and growth potential, which seems to demonstrate DiDi’s agility in calibrating its focus and resources.

Indeed, the company’s leaders have acknowledged the importance of thoroughly understanding each market, as every country and city has unique characteristics.As one company executive commented, “We don’t want to introduce all services everywhere. First, [we want to] understand the country and its needs. The mobility market is young, and people are thinking about how to move and how to buy things, which is something that DiDi is also investing in Latin America.” In line with this, the presence of Latin American employees with global experience at DiDi is notable. The company assembled a team that reflects the region’s diversity, with a workforce that boasts a large proportion of Mexican and Colombian professionals but also includes Chileans, Peruvians, and some North Americans with experience in the Latin American market, who have been educated in their home countries. By 2020, the company had around 1,500 employees in Latin America, the vast majority of them locals. This strategy appears to strengthen its connection with the community and its understanding of local business culture.

This strategy is part of a global approach. In a 2019 interview with the Xinhua News Agency, DiDi’s executive vice president, Zhu Jingshi, noted that to be successful, you not only need good products but also “to understand the customs and regulations of each region.” The article featuring the interview went on to say, “Unlike other companies in the sector, Didi created an international technical team that extends from Beijing to Silicon Valley, passing through different local markets.” Accordingly, many professionals at DiDi are relatively new to the company, having previously worked at local companies and sometimes even at competitors like Uber, Cabify, and Rappi. This diversity of experiences allows for better adaptation to local realities.

An interesting aspect is the contrast between this dynamic and the greater control maintained by Chinese expats in Chinese-owned companies in other industries around the world, such as mining operations in Africa or even early mining operations in Peru back in the 1990s. DiDi’s localized strategy seems to contrast with the approach of some Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which have tended to maintain stricter control by the Chinese parent companies and to rely more heavily on Chinese expat managers and workers. This difference likely stems in part from DiDi’s identity as a private technology company. The international experience of its managers and the company’s connections with global investors, including Uber and SoftBank, may also foster a more cosmopolitan culture. Furthermore, the company’s focus on profitability appears to contrast with the prioritization of natural resource security in the case of other investments. In this sense, the case examined here raises questions about the impact of ownership structure, founder backgrounds, and industry dynamics on the globalization strategies of Chinese companies.

DiDi’s Alliances with the State and Civil Society

One area that demonstrates DiDi’s adaptability in the region is its establishment of strategic alliances with actors such as governments and local businesses. These collaborations address issues such as road safety, public security, and gender equality. For instance, regarding road safety, DiDi has partnered with a nongovernmental organization called the Association of Traffic Accident Victims (AVIACTRAN) to promote responsible driving practices and road safety in Peru. In terms of public security, in Argentina and Chile, the company has allied with Prosegur, a private security firm operating in these countries, to provide necessary assistance in situations of insecurity that passengers and drivers may face. The platform allows users to call an emergency patrol through a panic button, which immediately connects them with Prosegur. DiDi can also monitor trips to detect if the vehicle enters an unsafe area.

Along the same lines, DiDi also established alliances and collaboration with local governments to address public security challenges, one of the most pressing issues in Latin America. A notable example is the implementation of the Law Enforcement Portal (LERT) in countries like Peru, Mexico, and Colombia. This platform allows government authorities to access real-time data on travel and mobility provided by the company. In this way, the company actively collaborates with governments and local authorities: “In the case of the Mexican market, the DiDi team met with State Prosecutor’s Offices across the country to train officials, judges, investigation agents, and officers in the use and management of the new portal.” While such data-sharing initiatives aim to improve public safety, they also raise potential concerns around surveillance and the handling of sensitive personal information, especially given past scrutiny of DiDi’s data practices in China. As these technologies are adopted in Latin America, it will be important to consider appropriate safeguards and oversight to prevent misuse.

Furthermore, as part of its corporate social responsibility initiatives, DiDi has announced its involvement in the creation of networks aimed at generating positive impacts in local communities. In Mexico, it announced commercial agreements with Vinco, an educational technology company, to benefit drivers and their families in educational matters. In Panama, the company formed an alliance with the National Institute for Women (INAMU) to support women at risk of violence who need to generate income. Also, in relation to violence against women, DiDi partnered with the Municipal Government of Chihuahua in Mexico to reinforce action protocols in situations of gender-based violence.86 Through this alliance, the Municipal Women’s Institute of Chihuahua would provide training to the staff of DiDi’s security center, responsible for responding to emergency calls, with the objective of providing timely assistance to female drivers, delivery workers, and passengers who might find themselves in risky situations.

Through these collaborations, DiDi has consolidated its presence in the region as a company committed to the safety and well-being of its users, especially women. Also in Mexico, the company implemented a mystery shopper program to create spaces for listening to the concerns of its female delivery workers in situations involving gender-based violence. Viridiana Ángel, who is affiliated with an advocacy group called Ni Una Repartidora Menos (Not One More Female Delivery Worker Lost), noted that DiDi was the first platform to approach them to listen and pay attention to their demands: “I am sure that with these improvements, we delivery women will feel safer.” These initiatives align with the company’s global efforts, which, according to the United Nations, have developed programs like “DiDi Women” to connect female drivers and passengers, improve perceptions of safety, and address inequalities through special economic incentives for female drivers. According to company representatives, in the last six months of 2022, there was a 46 percent increase in the number of women drivers using the platform in Peru. By addressing sensitive and urgent issues such as public security and gender-based violence, the company not only consolidates its presence in the region but also shows a capacity to understand and respond to the specific needs of the communities where it operates.

Integrating Taxi Drivers From the Formal and Informal Labor Markets

The ride-hailing sector, globally, has been a hotspot for protests and conflicts. At the heart of these conflicts lies the intensifying rivalry between conventional taxi drivers and those who work for ride-hailing apps. Conventional taxi drivers—bound by official rules related to city planning, traffic control, and road safety—struggle to compete with the more flexible and less regulated ride-hailing platforms. These platforms, often operating with fewer regulatory constraints, offer greater flexibility and convenience, appealing to a modern, tech-savvy customer base. In 2015, for example, taxi unions in Colombian cities such as Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, Cartagena, and Barranquilla protested Uber’s services. Similarly, a study conducted in Mexico highlighted the disputes that arose following Uber’s entry into the market, primarily between taxi drivers and app-based drivers. In Buenos Aires, taxi driver unions were involved in violent protests against Uber drivers, and they also filed formal complaints against the company.

As these protests escalated during the mid-2010s, DiDi began rolling out the DiDi Taxi feature in several countries across the region throughout 2019, including Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Argentina. Unlike other companies, such as Uber, which generated conflicts with taxi unions and associations, DiDi offered economic and technological opportunities to these traditional drivers, adapting to local needs. To participate in the DiDi Taxi service, drivers were required to hold a valid professional license and operate vehicles that met specific standards, such as being recent models equipped with air conditioning and airbags. This strategy presented several advantages for traditional taxi drivers, including the ability to receive card payments, complete more trips without periods of inactivity, and access relevant information about passengers before accepting rides. As the director of corporate affairs for the app in Chile asserted, “DiDi does not seek to disrupt the market, as most apps aim to do. Instead, we want to listen to and understand all the discussions taking place in the territories where we operate.”

However, this policy is not universally applied, as its implementation depends on the strength of the unions and their ability to coordinate effectively. This explains why the system has not been developed in countries like Peru, where the only option is to coordinate with private vehicles. To grasp the situation fully, one must consider the unique dynamics of the transportation system in these cities. Taxis often operate without proper metering, and the absence of well-organized, influential taxi unions leaves the sector vulnerable to unregulated competition. Moreover, the Peruvian government’s inability to effectively regulate passenger transportation services, even before the rapid rise of the gig economy, has further compounded the challenges faced by traditional taxi drivers. In such a context, DiDi builds direct relationships with private drivers, adapting to each locality’s unique circumstances.

When it comes to independent drivers, DiDi has employed aggressive campaigns to recruit as many drivers as possible by offering enticing incentives, such as waiving its commissions entirely for the first few months or providing minimum income guarantees. By waiving commissions, DiDi allows drivers to keep 100 percent of their earnings during the introductory period, making the platform more attractive to potential drivers. This approach was evident in Buenos Aires and Quito. In Chile, DiDi guaranteed a minimum income of $500,000 pesos (about $750 dollars in mid-2019 exchange rates) in the first week to the first 10,000 drivers who registered in Santiago, pledging to cover any shortfall if drivers failed to reach this amount.Another key factor in the company’s strategy is the low service rate it offers compared to other platforms in the region, ranging from 10 percent to 15 percent. In some cases, the company has resorted to this payment structure not only when entering new markets but also during times of economic crisis, such as in Peru in March 2023. During our fieldwork in Lima, we found that many drivers used DiDi, especially on weekends, when commissions were close to 0 percent. These cost-subsidizing strategies for drivers mirror those employed in China to compete with Uber and can be implemented regionally because of the company’s financial strength.

DiDi’s adaptability in the region is further demonstrated by its development of social support programs for partner drivers and passengers. For instance, during the pandemic, DiDi established a $10 million global fund to assist drivers and taxi drivers diagnosed with COVID-19 in its international markets, providing up to twenty-eight days of income support. In countries like Chile, the company also offered funds amounting to 10,000 pesos to drivers who had completed at least one hundred trips in March 2020, enabling them to purchase vehicle disinfection supplies. In addition to financial assistance, DiDi launched initiatives such as DiDi Hero, a program that provided free or discounted trips to over 6 million frontline medical and healthcare workers worldwide. In Mexico alone, the company invested 42 million pesos (nearly $2 million in July 2021) into this program, distributing 500,000 vouchers for trips and meals to healthcare staff. By offering concrete benefits and demonstrating empathy toward the challenges faced by drivers, DiDi sought to foster loyalty among its partners in a highly competitive market.

While these strategies showcase DiDi’s ability to adapt to various regional contexts, it is important to acknowledge that these strategies are not entirely unique to this company compared to other private platforms. However, one area where DiDi truly stands out from other platform companies is its expansion into a range of financial services. In Mexico and Brazil, the company introduced a debit card that enables drivers to receive income from rides, withdraw cash, and make purchases.Moreover, in 2021, DiDi launched Didi Préstamos (Didi Loans) in Mexico, a feature that allows both drivers and users to apply for loans of up to 30,000 pesos (approximately $1,750). The rapid growth of this service is evident, with the company reporting more than 500,000 loans issued in Mexico by September 2022, an amount that reached an impressive milestone of 5 million loans by June 2023. Furthermore, in late 2023, DiDi announced that Mexico would be the first country globally where the firm would offer the DiDi Card—a credit card with no hidden fees and a lifetime waiver on annual fees. DiDi further exemplified its adaptability and innovation through the introduction of the Club DiDi program in Mexico, which is designed exclusively for DiDi drivers and DiDi Food delivery partners. This program brings together a wide range of benefits made possible through partnerships with more than thirty companies. These benefits include discounts on vehicle parts and maintenance, access to microcredit facilities, vehicle insurance options, and attractive financing schemes for purchasing new cars.

DiDi’s expansion into financial services in Latin America mirrors its earlier strategies in China, where the company leveraged its massive user base and strategic partnerships to offer a range of services beyond ride hailing. Just as DiDi’s integration with WeChat in China allowed it to tap into the app’s widespread adoption of mobile payments, the introduction of debit cards, loans, and credit cards in Mexico and Brazil demonstrates the company’s ability to adapt to the unique financial needs and preferences of each market. By partnering with local companies and offering tailored financial solutions, DiDi is not only differentiating itself from competitors but also creating a more comprehensive ecosystem of services that caters to the specific requirements of its drivers and customers in the region.

DiDi’s Entry Into the Peruvian Market

Peru offers a striking example of how DiDi adapts to new markets. The Chinese ride-hailing giant entered the country in October 2020, a time when the sector was already dominated by established players such as Cabify, which had been operating since 2012, and Uber, which had been present since 2014. Other apps, including Beat and Easy Taxi, had also entered the market before, but eventually had exited because of the intense competition. Similarly, in the food delivery sector, DiDi Food faced stiff competition from Glovo (PedidosYa since 2021), which had been the first to offer food and product delivery services in Peru starting in 2017, establishing a presence in multiple cities like Lima, Arequipa, Trujillo, Piura, Chiclayo, Cusco, Ica, and Huancayo. Uber Eats and Rappi followed suit in 2018, with Uber Eats initially focusing on six affluent districts in Lima: Miraflores, Surquillo, Barranco, Surco, San Borja, and San Isidro.

The year 2020 marked a turning point for the platform economy in Peru, as it did in other countries in the region. The onset of the coronavirus pandemic brought about restrictions, with taxi apps only permitted to operate with drivers registered by the Urban Transport Authority and during limited hours. This led to a significant decline in demand until mid-2020, creating a challenging context for DiDi’s entry. The pandemic’s impact on the dynamics of transport companies was profound, prompting some, such as Beat and Uber Eats, to cease operations in Peru altogether.

Amid the economic uncertainty brought about by the pandemic, however, these platforms also emerged as a crucial lifeline for thousands of unemployed individuals, providing them with a source of income. Data from El Comercio, supported by the Permanent Survey of Employment of the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, revealed a substantial increase in the number of food delivery workers, rising from 21,000 in 2019 to 46,000 by the end of 2020. Notably, 73 percent of these workers relied solely on this occupation as their only source of income, according to the Peru Platforms Observatory.

Despite the challenging market conditions, DiDi’s entry strategy in Peru demonstrated its ability to adapt and innovate. The company focused on offering highly competitive rates to attract passengers, with fares starting as low as 5 soles (less than $2). Moreover, DiDi provided low commissions of 18 percent for drivers, significantly lower than the 30 percent charged by competitors at the time. This approach aligns with the strategy employed by DiDi in China, where it engaged in a price war with Uber, highlighting the company’s willingness to prioritize market share over short-term profitability.

Our fieldwork in Peru revealed that a primary reason behind drivers’ preference for DiDi was the potential hourly income. One driver highlighted DiDi’s reliability, emphasizing the bonuses and dynamic pricing that recognize and reward their work: “I have about 6,000 trips with DiDi, as it’s the most reliable of all apps. It’s the one that recognizes you the most because they give you bonuses, right? And there are dynamic rates that increase the cost when there’s traffic. DiDi is currently the most reliable [one] here.” Another driver highlighted the importance of DiDi’s weekend incentives, noting that completing a certain number of rides within a specific timeframe could yield a bonus, either as a percentage or a fixed amount.These incentives were crucial for both drivers and delivery workers, as the bonuses allowed them to earn a significant portion of their income while the fixed rates remained low to attract passengers. By offering competitive rates for passengers and appealing commissions and incentives for drivers, DiDi successfully captured substantial market share in Peru despite the challenging circumstances: the number of registered drivers increased by 30 percent in 2023, and the company reported over 3.5 million active users in Peru.

A second notable aspect in the Peruvian case, and in Latin America in general, is the emphasis DiDi places on safety. The company implemented a rigorous verification process for its partner drivers in Peru, which includes validating their driving licenses, ensuring the validity of the drivers’ mandatory traffic accident insurance, conducting background checks, and requiring that drivers’ vehicles be models from no earlier than 2006. According to a Peruvian newspaper editorial, DiDi has said that its Peruvian passengers “highly value that, in addition to an affordable price, the app they choose offers various safety options to protect them before, during, and after the trip.” Several drivers noted that these factors influence their own strategies. For instance, one driver mentioned using less secure platforms during the day when there is sunlight and there are more people on the streets, but almost exclusively using DiDi at night due to its higher level of security. Another driver recounted a remarkable incident where he received an unexpected call from the app after deviating from the recommended route. To his surprise, the company representative inquired about his well-being and the reason for the detour, ensuring that everything was in order during his trip.

Moreover, several interviewed drivers appreciated that, unlike other companies, DiDi does not force them to accept passengers in areas they consider dangerous. According to Francisco Oyola, DiDi’s security manager in Mexico, risk zones are created for the drivers’ safety based on information provided by authorities, AI algorithms that analyze the number of reported incidents from the platform, and feedback from the drivers themselves. This decision to allow drivers to avoid risky areas was not automatic. Initially, DiDi, like other platforms operating in Lima, imposed penalties on drivers who refused to pick up passengers, even in potentially hazardous locations. However, the company later changed its approach, granting drivers and delivery personnel more freedom to decide when to accept a job. This contrasts with other companies that, for example, do not specify the exact destination of passengers or only do so in very general terms.

During our fieldwork in Peru, several drivers emphasized that they would rather face penalties than risk having their vehicles stolen or being assaulted. They also mentioned that with so many platforms available, they could easily switch to another one while the penalty lasted. In this context of competition and workers’ resistance strategies, DiDi’s decision to prioritize driver safety makes sense and seems to distinguish the company. It is interesting to note that DiDi’s sensitivity to safety issues may stem from its recent history in China, where the company faced strong backlash and government scrutiny following violent incidents against passengers. Similarly, despite DiDi’s efforts to expand urban areas for passenger pickup and product delivery, one of the most appreciated practices by the interviewed delivery drivers was DiDi’s flexibility in allowing them to cancel a delivery based on their perception of the risk level in the area, without facing penalties. This flexibility is significant as it contrasts with the more rigid scheduling and location systems of other platforms.

DiDi’s adaptability to the Peruvian market is also exemplified by the introduction of flexible fare negotiation for its transportation services. In December 2022, the company launched the Didi Flex option in Peru, allowing passengers and drivers to propose and agree on trip prices. Although it was initially implemented by InDrive, a company formerly based in Russia, DiDi incorporated this feature in the Peruvian market because of its acceptance as a cost-saving measure among passengers. The success of this initiative in Peru prompted DiDi to expand the service to major cities in Colombia and Mexico. In March 2024, the company announced the launch of DiDi Set Your Price (Pon Tu Precio) in Chile, aiming to cater to users’ needs and preferences while maintaining the same security scheme as DiDi Express. The service is now available in other countries including Argentina, Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, Egypt, and Australia. DiDi’s strategy of initially testing the service in specific markets before expanding has proven effective. In Peru, nearly half of passengers chose this alternative at least once weekly, resulting in a 30 percent increase in registered drivers.This adaptability and responsiveness to local needs has been crucial to DiDi’s growth and success in Latin American markets.

These examples demonstrate DiDi’s ability to adapt to the evolving needs of users and drivers. By providing a sense of formality and safety for both drivers and passengers, DiDi addresses key concerns within the context of informal transportation in Peru. The company has tailored its driver registration and verification processes to accommodate the informal labor status of many potential drivers while upholding safety standards. Moreover, by allowing flexibility in fares through Didi Flex, DiDi acknowledges local market dynamics and the cost-saving strategies desired by passengers.

Finally, the Peruvian experience illustrates the ongoing negotiations between the company and local stakeholders. DiDi Moto’s launch in Peru in August 2023 marked an ambitious attempt at innovation that collided with legal barriers. The promise was to enable rapid urban transportation by allowing users to request motorcycle rides for personal mobility. In a country where informal motorcycle transportation was a common practice due to urban congestion, DiDi introduced its service without seeking special permits, assuming that its model, successful in other countries like Colombia and Argentina, would be viable in Peru. The company even aggressively promoted this new motorcycle service by incentivizing riders with the potential to earn up to 300 soles weekly (about $80, slightly above the minimum wage), enabling motorcyclists, including food delivery couriers, to sign up on the app.

However, DiDi’s assumptions clashed with a significant legal barrier in Peru. A 2019 law explicitly prohibits offering taxi services using motorcycles or linear motorbikes (small, single-track motorcycles) across the country. Peruvian authorities consider these modes of transportation risky for passengers because of high rates of traffic accidents involving such vehicles that have led to public security concerns. According to the National Transportation Administration Regulations (RNAT), taxi services must be provided exclusively using M1 category vehicles, defined as cars with three or five doors and side windows behind the driver’s seat. The Peruvian government’s response to the launch of DiDi Moto was swift and decisive. Citing concerns over user safety, the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC) instructed internet service providers to block the app. This measure not only impacted DiDi Moto but also disrupted the company’s other services, including passenger transportation through DiDi Express and food delivery via DiDi Food.152

The situation halted DiDi’s operations in Peru for nearly two weeks. Initially, the company issued a statement expressing its willingness to cooperate and engage in dialogue with the MTC to resolve the suspension, even requesting a meeting with the minister at the time. DiDi highlighted that the measure was causing significant economic losses for over 6,000 partner restaurants and impacting the livelihoods of approximately 150,000 delivery workers who depended on the platform to generate income. However, it was not until late August that the MTC unblocked DiDi’s services, allowing the company to resume operations. In a strategic effort to rebuild trust among passengers, drivers, and partner businesses, DiDi launched a series of attractive promotions, demonstrating its flexibility and commitment to its diverse user base in the face of regulatory blowback.

While DiDi assumed it could replicate its successful model from other countries, the company underestimated the responsiveness of Peru’s legal framework to address perceived public safety concerns. This episode showcases DiDi’s agility in adjusting its strategy and communication approaches in the face of setbacks, leveraging its relationships with users and partner drivers to facilitate a swift reactivation of services in the country.

Conclusion

This paper has analyzed how the Chinese company DiDi has adapted its strategies and operations to the specific dynamics of passenger and product transportation in Latin America. Drawing from its consolidation experience in the Chinese market and following a pattern of local adaptation, DiDi has tailored its approach, considering the socioeconomic, cultural, and regulatory contexts of the cities and countries it has entered. Although this process has sometimes faced challenges, such as the launch of DiDi Moto in Peru, the firm has made efforts to create strategic alliances with key local actors, such as taxi associations and local governments, to strengthen its market position. Facing the specific challenges of the region, such as safety concerns for drivers, DiDi has introduced technological innovations that allow users to be aware of potential risks, refuse trips in dangerous areas, and collaborate with local security companies and state authorities.

DiDi’s trajectory in Latin America offers valuable lessons about the strategies that Chinese companies employ to establish themselves in the region; their capacity to prioritize understanding and adapting to each country’s unique contexts stands out. This is reflected not only in company executives’ public statements but also in how the company tests different services and expands them to other countries when they prove successful. As noted at the beginning of this paper, information technologies not only connect distant spaces but also require active engagement with local environments to advance in different markets. From this perspective, this paper raises some questions: How do Chinese companies balance standardization and global adaptation? The case of DiDi suggests that adaptation is key, especially in cities with specific problems in terms of insecurity or informal labor forces. However, our work also suggests that it is crucial to continue exploring how local experiences from China can shape Chinese companies’ global strategies.

DiDi’s expansion in Latin America transcends simplistic narratives about the homogeneous nature of China’s economic presence in the region or the inflexibility of large Chinese companies. Instead, our preliminary findings suggest a trajectory that differs from that of Chinese SOEs, partly because of DiDi’s complex ownership structure. This compels us to seek to differentiate factors such as the sector in which a given company operates, the type of investors who fund it, or even the professional experience of its founders when analyzing Chinese global investments. Although this paper only briefly mentions Uber’s stake in DiDi, this detail hints at a potentially significant trend in the global digital economy. As companies become increasingly interconnected through cross-border investments, the traditional dichotomy between Chinese and Western firms may become less clear-cut. Future studies could explore how these ownership ties shape corporate behavior and market outcomes.

Through this research, we found that an aspect of the relationship between technology companies and working conditions that has not received sufficient attention in relevant public discussions is data privacy concerns and, more generally, the relationship between business and politics. In Latin America and the United States, critical voices have emerged in discussions about the impact of Chinese investments on technology, the energy sector, or infrastructure policies. However, this is only a part of a larger conversation. It is also important to note that, in places like Peru, it has not been possible for DiDi to establish this dialogue with a state with strong capacity: collaborations are primarily established with civil society actors when they exist. Moreover, while issues regarding data privacy have been a central issue in China, the discussion on this matter by political actors is practically nonexistent in Latin America. DiDi’s collection of user data raises important questions about the protection of personal information and the potential for its misuse by either market or state actors, highlighting the need for robust data protection frameworks in the region.

Omar Manky is an assistant professor of social sciences at the University of the Pacific and a researcher at the Center for China and Asia-Pacific Studies (CECHAP) and the Research Center of the University of the Pacific (CIUP). Natalia Mogollón has worked as a research assistant at the Center for China and Asia-Pacific Studies (CECHAP) and is a consultant.

This article is an excerpt of a research paper published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Republished with permission.