How Central Banks Saved Latin America

How Latin American central banks crushed inflation, tamed populists and saved the economy.

BY JOHN PRICE

For those of us foolish enough to try to forecast Latin American economies, there is a new factor to consider — the central bank policies and target interest rates of Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Colombia.

Not long ago, central banks in Latin America served a perfunctory role through most of the business cycle, following the US Fed rate hikes and cuts, maintaining a steady premium over the US treasury rate. When Latin American central banks did act boldly, it was to hike rates in a last-ditch effort to stem capital flight in time of crisis, starving local markets of capital just when liquidity was needed.

The COVID crisis illustrated that times have changed. When markets hit the panic button and capital began to leave emerging markets (and just about everywhere) to a handful of global safe havens — like the US dollar, the Swiss franc, the euro and the Japanese yen — Latin America’s central banks did NOT hike interest rates. Instead, they dropped their rates and kept their domestic capital markets liquid. Such an historic policy shift prevented tens of thousands of indebted companies from going out of business, as so often happened in previous downturns, like the financial crisis of 2008-2009.

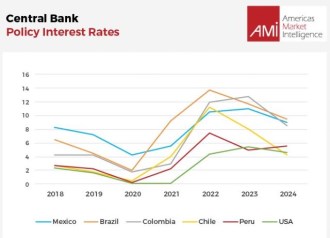

Latin America’s leading regional central banks surprised economists again in 2021 and 2022 when they began aggressively hiking interest rates more than a year ahead of the US Federal Reserve. Since mid-2022, the Mexican peso and Brazilian real have been two of the best-performing currencies in the world and 2023 has proven to be a year of regional economic expansion, a fact that almost no one saw coming. Today, the central banks of Brazil and Chile have tamed inflation. Mexico and Peru will follow suit by the end of 2023. All four will beat the US Fed to the inflation-conquering finish line.

HOW THIS HAPPENED

Why are Latin America’s leading central banks now so effective at shaping their economies where in the past they were powerless to do so? When did this happen? Like most good things, Latin America’s autonomous, well resourced, and professionally run central banks took time to develop — over 20 years in fact.

Curiously, the modernization of Latin America’s financial authorities (and that of many around the world) began in Canada in 1998. In the aftermath of the 1997 Asian market crisis that took down currencies in Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines, among others, Canada’s ambitious Minister of Finance, Paul Martin, and his Financial Institution Superintendent, John Palmer, put their heads together and created the Toronto Centre, where the world’s emerging market financial regulators and supervisors would be schooled in best-in-class management. One to two-week intense courses were designed to professionalize all aspects of financial regulation and supervision, including many of the responsibilities pertaining to a central bank. Today, 25 years later, hundreds of the senior government financial technocrats around the world owe their professionalism to the teachings learned in Toronto from master-class instructors, recruited from the world’s leading financial regulators and central banks. The Toronto Centre’s most prolific alumni cluster is found in Latin America, where governments responded enthusiastically to the instruction offer, subsidized by the IMF and the Canadian government.

The working knowledge taught in Canada and perfected in action over the last quarter century has given Latin America’s leading central banks and financial supervisors the confidence to build institutional cultures of high standards and unbendable autonomy. That has served them well during the latest wave of elected populists, many of whom (Brazil, Mexico, Colombia) have butted heads with their central banks and other financial institutions but heeded to their institutional independence. It is not an exaggeration to say that today’s central banks not only buffered their economies from economic downfall during COVID and the ravages of post-COVID inflation, but they also prevented the populists in office today from acting upon reckless economic impulses.

Over the last two decades, the professionalization of Latin America’s central banks has given political weight to technocrats in the ministries of finance and their allies across the executive branch to push through often-overlooked reforms. Small rule changes helped equip central banks with essential tools, and created savings mechanisms (pension funds, national reserves) that kept monies inside the country, an essential backstop that lessened capital flight in times of crisis. It is this institution building, brick by brick, of central banks, pension systems, capital markets and national reserves that separates Latin America’s leading economies (Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru) from all the rest.

When people reflect upon the leadership heroes of Latin America, they don’t think about central bankers or financial institution technocrats, but they should. Thanks to the professionalism of Latin American leading central banks, the region’s economy is sounder, less volatile, and better capitalized than ever before. No institution has been more effective at defanging the destructive impulse of political populism than the Latin American central bank and the global flows of capital that their policies influence.

Economic sovereignty begins by convincing investors to keep their monies invested at home. The only way to do that is to build a legal and financial institutional foundation that instills confidence in investors. Latin America’s central banks have done more to engender such confidence than any politician in the region. By doing so, they now have a voice in the future direction of the region’s economies. That is a good thing, even if it makes Latin American economic forecasting more complex.

John Price is the Managing Director of Americas Market Intelligence. With 20 years of experience in Latin American market intelligence consulting, Price has supervised nearly 1,200 client engagements and advises clients in more than 20 countries across Latin America. He can be reached at jprice@americasmi.com

This article was first published by AMI. Republished with permission.