Dollarize Argentina; Abolish the Central Bank

The case for dollarization and closing the central bank in Argentina.

BY JOHN GREENWOOD

WITH STEVE H. HANKE

AND FRANCISCO ZALLES

Over many decades the stability and value of the Argentine peso has been repeatedly undermined by successive governments in Buenos Aires who have relied on the monetary powers of the Argentine central bank to fund budget deficits. This has led to persistently rapid broad money growth, high inflation, and a chronically weak currency. To end the abuse of the central bank we propose abolishing the BCRA and dollarizing the economy. In 1999, at the invitation of Pres. Carlos Menem, Steve H. Hanke and Kurt Schuler first proposed that the Argentine economy be dollarized. The first thing to do is to establish a market exchange by ending capital/exchange controls and allowing the currency to float freely for a month before locking into a fixed exchange rate. After Dollarization-Day, all peso- denominated assets, liabilities, and contracts would be replaced with USD at a fixed rate, and outstanding peso banknote issues would be exchanged for USD banknotes over a period of 6-9 months. To deal with any shortage of coins, the government would mint new USD-denominated coins with Argentine symbology to replace worthless peso coins, the new coins to be backed 1:1 with US$ paid for by the banks when they order cash for their customers. The important short-term money market in peso-denominated LELIQs would be replaced with US$-denominated government securities to be issued and redeemed by a new, independent office for Argentine government debt – along the lines of the British DMO. Under this plan, inflation and interest rates could be expected to fall rapidly. There is nothing special about the Argentine case that prevents dollarization, only lack of knowledge of the correct procedures and the political authority to implement them.

1. Introduction: The Overall Justification for Dollarization

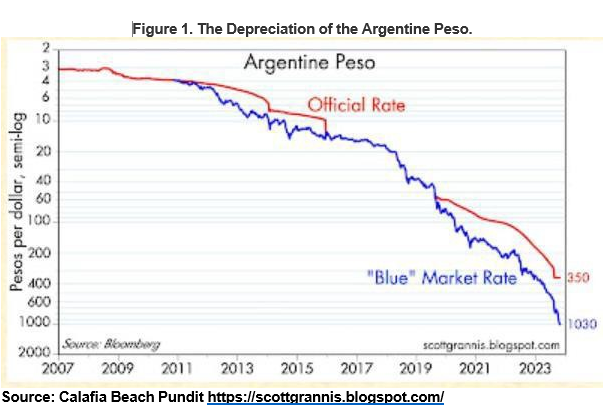

The stability and value of the Argentine peso has been repeatedly undermined by successive governments in Buenos Aires relying on the monetary powers of the Argentine central bank, Banco Central de la República Argentina (BCRA), to create money to make up for revenue shortfalls of high-spending administrations. Since January 2018 alone, the value of the Argentine peso has plunged from an official rate of ARS19.6 per USD to 350 per USD in November 2023. But the official rate is not a market rate. The “blue” rate for the Argentine peso, a parallel or more realistic exchange rate has recently been trading at 910 for buying and 960 for selling. Probably a free-market rate would be somewhere between the official and the “blue” rate. In either case, the peso has depreciated drastically. As Keynes wrote, “By a continuing process of inflation, government can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens”. The process of inflation transfers purchasing power directly from private sector holders of money to the government. It is, in effect, outright robbery.

The presidential election of November 19 creates an opportunity for the Argentine people to end the persistent abuse of their currency once and for all. The people of Argentina must never again allow their government to abuse the central bank at their expense. The best way to do this would be to move to a monetary system where the government or fiscal authorities have no access to a central bank. In Argentina’s case, this means abolishing the BCRA and dollarizing the economy as first proposed at the invitation of Pres. Carlos Menem by Steve H. Hanke and Kurt Schuler in 1999.

In the future the government would maintain its accounts at various commercial banks, which would act as paying agent for the government, as they do for any other customer (as happens in Hong Kong and Panama). Such a move would strengthen fiscal discipline, imposing a hard budget constraint on the government. In future, government finances will be sourced solely from (1) tax revenues and earnings of public sector corporations, (2) drawing down on accumulated past surpluses or (3) issuing USD-denominated debt to finance deficits. The government would no longer be able to rely on the central bank as a clandestine, hidden source of funding.

In carrying out these monetary and fiscal reforms, politicians and administrators would be compelled to engage in serious institutional changes – possibly amounting to constitutional amendments. No longer able to print money to fund projects at will, Argentine governments would be compelled to move their budgets much closer to balance. The budgetary oversight process could be strengthened, and a much higher degree of transparency could be introduced. While such reforms are not a cast-iron guarantee against abuse or corruption in future, they would eliminate monetary tampering. Excess fiscal spending is still possible (as has occurred in Ecuador and Panama), but only by running up large debts and persuading foreign governments and foreign investors to part with their funds. At the least, ending government access to the central bank would eliminate the kind of abuse that has led to repeated cycles of growth, debt, and devaluation because the nation’s currency would no longer be Argentine pesos. It would be US dollars whose value is beyond the control of Argentine politicians, and the BCRA would no longer exist.

At this stage it should be mentioned that if dollarization is not carried out in the next year or so, there is a non-negligible chance that dollarization may be forced even on an unwilling government by circumstances. For example, the Argentine people already hold substantial quantities of US dollars (said to be worth between $200 and $260 billion) in physical cash and deposits. Yet despite all the government restrictions on use of the US unit and multiple, discriminatory exchange rates, they are still able to conduct many transactions in US dollars. The authorities are fighting a losing battle to keep the peso.

2. Dismantling the BCRA

2.1 Basic Principles

Over past decades the BCRA has acquired many functions in addition to its narrow monetary functions. We now propose to dismantle the central bank, eliminating its money-creating powers and shifting its other activities to alternate agencies.

The process of dollarization requires the recognition and adoption of two basic principles. First, an announcement should be made that all contracts currently in pesos will be converted by decree to USD contracts at a fixed exchange rate at a future date (Dollarization-day or D- Day) and time to be specified. Second, after a period of (say) 30 days from the date of this announcement, the prevailing exchange rate will be adopted as “the” exchange rate which will be used to convert all existing peso contracts into USD contracts from that day forwards. This is exactly what was done in the case of Bulgaria in 1997, on Steve Hanke’s advice, to determine the new, fixed exchange rate. The outcome was a very rapid fall of consumer price inflation from over 2000% in 1997 to 22% by March 1998, 4% by August 1998, and an average of 2.5% for the year 1999 as a whole. During the one-month period of floating, the monetary base should also be frozen, again as was done in Bulgaria, effectively mothballing the BCRA immediately.

In essence this means that all peso obligations of the BCRA (and the government) will be converted to USD obligations. However, there is one exception: the outstanding peso banknotes which are liabilities of the BCRA will need to be paid out as rapidly as feasible in USD banknotes. All other items on the balance sheet of the BCRA – or on the balance sheets of commercial banks or companies or individuals – constitute “claims” or I.O.U.s for Pesos (or ARS) and can therefore readily be translated at the selected D-Day exchange rate to USD- denominated claims or I.O.U.s. This applies to all contracts, public and private, whether for deposits, loans, rents, wages, interest, and dividends, or complex instruments such as futures contracts or derivative contracts. It also includes the entire market for LELIQs, or Letras de Liquidez, Liquid Bills and Notes issued mainly in Peso currency by the BCRA (see section D below). Instead of being Peso-denominated, these contracts and their associated interest rates or yields will all become USD-denominated claims and obligations on or after Dollarization- day, or D-Day.

2.2 Treatment of individual items on BCRA’s balance sheet

A.1. Cash Currency or Banknotes and Coins.

Currently (using data for Oct 23, 2023) the BCRA has outstanding banknote issues and coin amounting to ARS 5,900 bn. In Table 1, gold and foreign exchange reserves amount to ARS 8,593 bn, divided into gold (ARS 1,372, or 16% ) and foreign currency reserves (ARS 7,221 bn, or 84%). However, these values are translated at the highly unrealistic, official exchange rate of ARS 350 per USD. According to the BCRA’s website, the central bank’s international reserves amounted to US$ 20,977 million on November 13, 2023. If a more realistic exchange rate closer to the “blue” rate of 900 per US dollar was used, the value of Argentina’s gold and foreign exchange reserves is closer to ARS 18,879 billion, over three times what is needed to redeem all outstanding peso banknotes at a market exchange rate.

The banknotes could be called in for redemption from D-Day at the chosen, fixed exchange rate. The period allowed for redemptions by the public can be generous – say with a deadline of up to twelve months from D-Day. This will reduce any sense of panic and allow people to continue to use Peso banknotes in place of coin alongside US dollar banknotes at the (now) fixed exchange rate. The redemptions of peso notes will take place mainly at commercial bank branches; there should be an option, but no requirement, for the redemptions to occur at the BCRA. Argentineans should be told the source of the USD they will receive, namely the country’s gold and foreign exchange reserves – which are ultimately the property of the citizens of Argentina anyway. Also, the underlying figures for outstanding peso banknotes and new USD banknotes estimated to be put into circulation could be published on a daily basis to avoid any panic conversions.

Supplies of US dollar banknotes could be ordered and obtained from the Federal Reserve System (normally from the Miami branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta) by the BCRA before its dissolution, or by individual commercial banks from their US affiliates and counterparts. It would be courteous, in this context, to notify the US Treasury and the Federal Reserve System in advance of the increased demand for US dollar cash currency.

The peso coins currently in circulation need not be exchanged and could continue to circulate until reversal of the necessary provisions of the Ley de Convertibilidad which established the current Peso in January 1992. In practice, Peso coins are now worth so little due to the massive depreciation of the peso that they are seldom used. Going forward, the Argentine Treasury (not the BCRA) should mint new US$-denominated coins in the same denominations as US coinage but bearing Argentine symbols. The banks would purchase these new coins for their customers, paying US dollars, and the Argentine Treasury or Ministry of Economy would be required to hold a 100% US dollar reserve against the coins issued (like a miniature Currency Board). In this way, soundly backed new coins would enter circulation alongside US dollar bank notes, and the old peso coins would gradually disappear.

- Bank Reserves. Currently, banks hold reserve deposit accounts at BCRA (amounting to ARS 1,154 bn on October 23) to meet legal reserve requirements and/or to make settlements with other banks and/or to make tax payments to the government on behalf of customers. After dollarization, these reserves would be translated into/expressed in USD at the chosen exchange There is no need for conversion in the foreign exchange market. The reserve requirements at BCRA could be eliminated and/or replaced with other balance sheet ratios enforced by a new agency for financial supervision which is not part of the central bank. (This is done in many countries, notably in Canada.)

Following dissolution of BCRA, commercial banks could operate the two clearing systems currently operated and supervised by the BCRA: (1) SML or Sistema de Pagos en Moneda Local – a Real Time Gross Settlement system that operates in Pesos and USD – and (2) CCE, or Camara Compensadora Electronica, an automated clearing house (ACH) which operates as an interbank clearing house, settling transactions on a net basis at the end of the day. Ideally, reserve balances at the BCRA will be transferred to these clearing houses.

B. BCRA as banker and provider of credit to the government.

Eliminating the ability of the BCRA to provide credit to the government is central to the task of ending Argentina’s inflation. The provision of deposit accounts to the government would also be eliminated. The government accounts could be moved to one or more private, commercial banks, just as occurs in Hong Kong.

C. BCRA as foreign currency agent for the government.

This function could also be transferred to an international or supra-national agency (such as the IADB or BIS) or, after a bidding process, to a private sector bank – domestic or foreign.

D. BCRA as operator of the LELIQ market.

The elimination of BCRA as operator of the short-term LELIQ market and the conversion of LELIQ securities to US dollars is perhaps the most controversial proposal here. (Several commentators have expressed the need either for LELIQ bills to be paid out to creditors as quickly as possible and treated as secured debt second only to Base Money, or for a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to be created so that the market can be continued in some form.)

To understand the true position, consider the market for EFBN in Hong Kong. This market was set up in the 1990s because the Hong Kong Monetary Authority wanted to create a local currency yield curve, but due to annual budget surpluses, there was no government debt available in Hong Kong on which to build such a yield curve. The HKMA therefore issued paperless, electronic debt instruments itself, known as Exchange Fund Bills and Notes, using the old name for the Currency Board, the Exchange Fund. Initially these short-term debt securities were auctioned on a frequent basis, with the proceeds held by the HKMA in its portfolio. Currently the amount outstanding is approximately HK$1,228 billion (or US$ 157.5 billion). Because the EFBN are liabilities of the HKMA, they can readily be discounted or sold to top up banks’ clearing balances. Since it is a rule of the clearing house in Hong Kong that banks must maintain positive settlement balances (they cannot become overdrawn), the main buyers of EFBN have been banks which use the EFBN to manage their short- term liquidity positions.

In many respects the Argentine LELIQ market is analogous to the EFBN market, except that the disposition of the proceeds by the BCRA (into Non-transferable Bills of the National Treasury) is considerably more opaque, and the reliability of ultimate repayment is much more doubtful. The LELIQ market (literally, Letras de Liquidez, or Liquid Bills and Notes issued mainly in Peso currency) is a segment of the Argentine money market where the central bank of Argentina (B.C.R.A.) auctions short-term liquidity bills (LELIQs) to local banks in order to manage the amount of money in circulation and influence the interest rate. LELIQs are mostly denominated in pesos and have different maturities, ranging from 7 to 28 days. The BCRA has typically set the floor rate for LELIQs, which serves as the benchmark rate for monetary policy and lending in the economy.

Proceeds of the LELIQ auctions are invested in “Letras Intransferibles del Tesoro Nacional” (Non-transferable Bills of the National Treasury). As shown in Table 1, on October 23, 2023, the outstanding amount of LELIQs had reached ARS 23,542 billion (US$25 billion at a “blue” mid-market exchange rate of 935, or $67.3 billion at the official 350 exchange rate). The non-transferable assets corresponding to the LELIQs were the largest component of the ARS 39,432 billion of Government Debt held by BCRA. In reality, this is a scam, comparable to the scheme in Lebanon, where the central bank of Lebanon issued high-yielding debt to attract funds from the banks but has never repaid any of it.

The LELIQ market was created in August 2018 as part of a new monetary policy framework that allegedly aimed to curb inflation and stabilize the peso, which had been depreciating sharply due to a loss of confidence in the government’s ability to repay its debt. The BCRA adopted a zero-growth target for the monetary base (sic!) and committed to sell LELIQs at rates necessary to absorb any excess liquidity in the market. The floor rate was initially set at 60%, but it has fluctuated over time depending on the inflation outlook and the exchange rate pressures.

Irrespective of these announcements and the introduction of LELIQs – however well- intentioned – M3 growth and monetary base growth have soared, and inflation has sky-rocketed. These developments have naturally increased both the nominal and the real cost of credit for the private sector and the government.

For present purposes – dollarizing the Argentine economy – we need to decide how to treat the LELIQs. There seems to be no reason why the two principles set out should not apply. LELIQs are IOUs to be treated like any other IOU. They should therefore be subject to the same decree, converted at the chosen fixed rate to US dollar obligations from D-Day. The outstanding total amount could be transferred from the balance sheet of the BCRA to the balance sheet of the government. Insofar as the BCRA was a government entity, the debt was and is ultimately payable by the Argentine government anyway.

Going forward, maturing issues could be redeemed in US dollars (at the D-Day exchange rate), and new issues could be auctioned by a new department set up within or outside the Treasury or Ministry of Economy. This would parallel the role of the Debt Management Office (DMO) in the UK, which is an Executive Agency of HM Treasury, established by the UK government in April 1998 with responsibility for government wholesale sterling debt issuance (popularly known as gilts), and transferred from the Bank of England. (https://www.dmo.gov.uk/)

Banks could continue to use the new USD-denominated LELIQs for managing their short-term liquidity if they chose to do so or sell them for USD cash in the market (after D-Day) or redeem them with the Argentine government (in USD after D-Day). Interest rates on LELIQs are likely to fall abruptly as D-Day approaches, and thereafter they would trade at a spread over equivalent US rates. The spread would be determined by the creditworthiness of the Argentine government, as viewed by market participants.

In the past, the LELIQ market has naturally been affected by political and economic developments in Argentina, such as IMF bailout agreements, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the presidential elections, and no doubt it would continue to be affected by such factors in future. Going forward, there might be a demand for the maturity of USD- denominated LELIQs to be extended beyond the current 28-day term of Peso- denominated LELIQs, and the new Debt Management Office would clearly need to decide whether to increase supply in this way. There would be no need, however, for any government agency to be setting any floor rate for USD-LELIQs as the BCRA did with Peso-denominated LELIQs. The auctions and the free market would set the yields for LELIQs.

Argentina would no longer have a monetary policy; it would only need to concentrate on ensuring the solvency of the government in USD terms. The supervision of banks and other financial institutions could be transferred to an independent financial sector regulatory agency (similar to Canada’s OSFI, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions).

The role of the B.C.R.A. in conducting repos (repurchase agreements) and derivatives would disappear. If banks needed a tri-party repo market in future where a third entity acts as an intermediary between the two parties to the repo, it could be provided through individual clearing banks (just as JP Morgan Chase and Bank of New York Mellon do in the US) or through a centralized clearing system or exchange operated by a central counterparty (CCP) such as operates in the US and in Europe and the UK.

E. Other liabilities.

The balance of Other Liabilities is composed mostly of either inter-government or bi- lateral agreements with foreign countries and international organizations, and there is little or no exposure to the private sector. Many of these liabilities are offset with corresponding asset entries such as SDR facilities. These could all be assumed by the Argentine government on an interim basis until a decision is made about how to participate in supra-national organizations such as the IMF and BIS.

3. Concluding Remarks

The plans set out here to dollarize the currency of Argentina broadly follow the templates used in Montenegro, which successfully adopted the Deutschemark in place of the hyperinflating Serbian-Montenegrin dinar in 1999 (and now uses the euro in place of the German mark), and in Ecuador, which dollarized the sucre in 2000. In addition, lessons learned in setting the exchange rates of the currencies of Hong Kong in 1983 (when a currency board was re- introduced to stop the collapse of the Hong Kong dollar) and Bulgaria in 1997 (when a currency board replaced a hyperinflating domestic currency) have also been applied.

There is nothing especially complicated or unique about the Argentine case provided the two principles explained at the start of this plan are followed. Within a matter of weeks, the Argentine people could be benefitting from a stable, global currency, sharply lower interest rates and a dramatically falling inflation rate. However, the success of the plan will depend – in the long-term – on the willingness of the Argentine government to play its part and not to engage in unsustainable borrowing to finance ambitious and extravagant welfare or infrastructure programs financed by debt. Nobody on earth can guarantee the good behavior of the country’s rulers except the citizens of Argentina. Reforming the currency should therefore be viewed as just part of a series of deep and far-reaching institutional reforms that set the country on a path to a better future.

Ideally those reforms will include strict limits on government budget deficits, the level of government debt, or any increase in taxation. The National Congress must have authority to monitor government expenditures so that a breach of any pre-set limit on the deficit or an increase in taxes or an expansion of the national debt should require super-majorities in the Congress. Whatever the mechanism, it is essential that, having ended the ability of Argentine politicians and governments to abuse the currency by excess money-creation through a central bank, they are not permitted to attempt the same kind of abusive property theft through fiscal means.

John Greenwood (john@internationalmonetarymonitor.co.uk) is Chief Economist at International Monetary Monitor Ltd., an economic consultancy based in London, England. He is also a Fellow of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise at JHU. Until December 2021 he was Chief Economist of Invesco.

The author would like to acknowledge helpful suggestions from Dr Kurt Schuler.

Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics and Founder and Co-Director of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. From 1989 to 1999, he advised Argentina’s Pres. Carlos Menem. In 1999, at Pres. Menem’s request, Hanke and Kurt Schuler drafted a dollarization law for Argentina. Hanke is a veteran of Argentina markets. He served as the President of Toronto Trust Argentina in 1995, when it was the world’s best-performing emerging market mutual fund.

Francisco Zalles is an adjunct scholar of the Ecuadorian Institute for Political Economy, and a past professor of economics. He has frequently participated in various forums on dollarization and money.

This article is based on a working paper published by Johns Hopkins Studies in Applied Economics. There are several tables and figures that are not included in this republication. The full version is available at https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/miqbqnfvlvfoz6sj2rnru/Working-Paper-245.pdf?rlkey=gr75uiycr4zd8d4dgobtvtii3&dl=0

Republished with permission.